By Jorgen Hesselberg and Roshelle Ritzenthale

Right before our eyes, our physical and digital spaces are converging. Augmented realities are creating a new genre of place-making that recognizes the opportunity for overlap between our physical built-environment and the digital experiences.

The biologist E.O. Wilson could likely not have predicted in his 1998 book Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge the extent to which knowledge from the specialized fields of digital and physical architecture could cross disciplines to create these new experience frameworks. The central idea that Wilson did recognize, however, is that all knowledge is inherently unified and interrelated despite the disciplinary divides we create—and more importantly, there is great potential in recognizing the consilience.

We’re just beginning to grasp the potential overlap between physical and digital space. Most of the time the convergence is forced or fragmented. Software architects, designers and planners speak in different languages from those same roles in the physical space.

One of the unifying languages is Agile.

In 2011 we landed on a unique opportunity to work with the architectural design firm Gensler to explore this consilience—an Agile technology company at odds with their decidedly un-Agile workplace. How can designers of the physical space integrate Agile methodologies—typically reserved for the digital sphere—into a responsive, participatory approach to workplace transformation? Can we speak the same language?

A Case Study: Agile Places for Agile Processes

A Fortune 500 company with operations in Chicago had adopted Agile development and business processes as part of an organization-wide transformation effort—yet the improvements were not as significant as expected. Team collaboration was lacking, software quality improved only incrementally and employee engagement scores were suffering.

After taking some time to listen to employees through anonymous surveys, interactive Open Space sessions and focus groups, the Agile Working Group (AWG) realized the current open plan cubicles were an impediment to organizational agility and getting work accomplished.

They were not alone. Long work hours, smaller workspaces and new and evolving technological distractions are challenging the effectiveness of the typical workplace. Simply stated, we are finding that open plan isn’t as flexible, fit-to-purpose—and Agile—as we had originally envisioned. Instead, it’s become a relatively unchanging, one-size-fits all, efficiency solution that organizations have tried (and by some standards failed) to cram a variety of work processes into.

Within this context, our team spotted an opportunity—what is the overlap between the approach to software design and the approach to workplace design? As workplace designers, can we hack Agile methodologies? What can we learn from our clients’ expertise in Agile that will make workplace design more effective—and more responsive—to the ever-changing needs of our clients?

Four Values inspired by the Agile Manifesto Applied to Workplace Transformation

- Individuals and Interactions over Processes & Tools:

Executives realized people affected by the change needed to be deeply involved in designing their own workspace. The employees were viewed as customers — and finding a solution that helped solve the problem of effective collaboration was the goal of the effort. The company decided to form a “Move Guild” consisting of representatives from Gensler’s workplace design team, facilities, organizational change management and several people from the product development teams. Each member of the team brought a unique and important perspective to the effort — and the interaction between the members of the Guild helped provide a diverse view of the workspace and ensure people directly affected by the move had ownership from the start.

In this approach, the value workplace designers brought to the creation process was now distributed across the roles of the Guild. In its place, design facilitation was a much bigger part of the workplace designer’s role, as was deep dive research into the change drivers that made this workplace and organization different from any other—its organizational objectives, change driver and most importantly, its people.

- Working Solutions over Comprehensive Documentation:

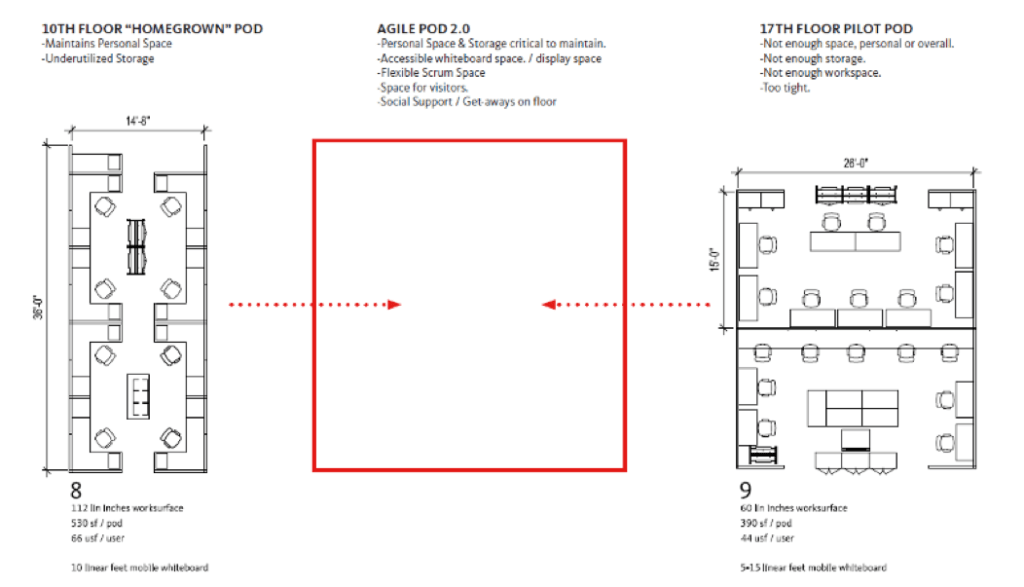

Leveraging the Lean Startup concept of Build-Measure-Learn, the Guild realized it was going to receive more meaningful feedback when building working solutions (Minimal Viable Products — MVPs) that could be validated with customers instead of imagining how people would like the workspaces based on sketches and elaborate drawings. Following Agile and Lean Startup practices, the team therefore built working prototypes of a select number of proposed designs — eventually called “poor man’s Pods” — that helped the Guild gather valuable feedback along the way. These prototypes — typically leveraging existing build materials — became short-term, affordable experiments with the sole purpose of validating architectural design assumptions and generate rapid insights.

These “poor man’s Pod” prototypes differ significantly from the typical workspace. The average workspace is a container—a pristine and relatively constant environment that is one-size-fits all—prototypes are a tool that allow for variation, iteration and user-directed self-control. It’s not perfect, photogenic or pristine.

In fact, it was a little messy.

- Customer Collaboration over Contract Negotiation:

The MVPs provided very unambiguous information — and was overwhelmingly negative. Despite the best intentions from the Guild, the initial models simply did not meet the needs of its customers: the workspaces were not only too small for associates to collaborate effectively, basic considerations regarding personal space and privacy and remote workers had to be re-thought completely.

For instance, the initial assumption was that having co-located space would save square footage per associate — and the designs supported this theory. After feedback from the pilot pods, it became clear the proposed space was simply insufficient and the designs needed to be changed to significantly increase the size of the PODs to support collaboration while respecting personal space.

Despite the initial sting of the negative feedback, the Guild relished the fact that having this very candid information early gave clear direction on what needed to be changed. Rather than sticking to the original plan the Guild took the customer feedback into account and redesigned the PODs to accommodate more space.

- Responding to Change over Following a Plan:

The Guild focused on outcomes — not output. The outcome they wanted was a collaborative, inviting workspace that supported creative people and energized an organization going through tremendous change. This meant that sticking to a strict, upfront plan was not considered critical: it was more important to have the architectural solution evolve over time, within shorter time boxes.

The designs evolved iteratively to not only accommodate privacy by adding “privacy booths” and increasing square footage per person, the workspaces were configured to be “hackable” — enabling lots of latitude for employees to customize and personalize within the framework of the PODs. As the PODs evolved, the PODs themselves became manifestations of the team’s identities. For instance, one team decided to set up an informal Xbox tournament with other teams in the business unit, helping to build internal team cohesiveness and relationships across teams. Another team decided to arrange a food drive to help the homeless in Chicago.

The designs evolved iteratively to not only accommodate privacy by adding “privacy booths” and increasing square footage per person, the workspaces were configured to be “hackable” — enabling lots of latitude for employees to customize and personalize within the framework of the PODs. As the PODs evolved, the PODs themselves became manifestations of the team’s identities. For instance, one team decided to set up an informal Xbox tournament with other teams in the business unit, helping to build internal team cohesiveness and relationships across teams. Another team decided to arrange a food drive to help the homeless in Chicago.

The designs evolved iteratively to not only accommodate privacy by adding “privacy booths” and increasing square footage per person, the workspaces were configured to be “hackable” — enabling lots of latitude for employees to customize and personalize within the framework of the PODs. As the PODs evolved, the PODs themselves became manifestations of the team’s identities. For instance, one team decided to set up an informal Xbox tournament with other teams in the business unit, helping to build internal team cohesiveness and relationships across teams. Another team decided to arrange a food drive to help the homeless in Chicago.

Remote workers were also considered in the design: At first, the teams experimented with immersive virtual workspaces, but application inefficiencies caused the teams to scrap the idea. Instead, remote workspaces were brought closer by investing in technical infrastructure to support serendipity and always-on connections. So-called “wormholes” is an example that teams leveraged in which large, high definition video screens provide very visible updates to status and served to minimize the distance between onsite and offsite teams.

Future-Focused

The effects of the Agile workplace transformation have had a marked impact on the organization. There are visual signs of team engagement and ownership everywhere — a “Pimp My Pod” competition in which teams were encouraged to transform their pods for the holidays prompted strong visible evidence of highly engaged teams—and people had fun while they were at it. Product development members report that meaningful face to face communication and collaboration between team members has increased — some days the need for phone calls, email and IM disappear completely. Perhaps the most tangible result is engagement scores: since our project began engagement scores have consistently gone up and are now among the highest across the company. Not a trivial fact when considering Chicago’s increasingly competitive search for top technical talent.

From the perspective of designers—representing both physical and digital realms—we are only at the cusp of recognizing the potential of a shared understanding of our relatively distinct schools of thought. Work is a state of mind. The office is an experience that happens anywhere, and the cloud is a place. Technology is a material—not unlike walls, paths and furniture—that can be layered and shaped. And conversely, physical space is a tool that dries interactive user-driven experiences—not unlike our smartphone apps and wormholes.

The future of work will not be the places and technology we know today, and co-opting Agile software development thinking to transform how we harness the power of place is just the start.

Jorgen Hesselberg is a co-founder of Comparative Agility, the world’s largest agile assessment and continuous improvement platform. He is the author of the upcoming book “Unlocking Agility” (Addison-Wesley) and has led major transformations for companies such as NAVTEQ (HERE), Nokia, McAfee and Intel. He is currently leading the digital enterprise transformation at Statoil.

Roshelle Ritzenthaler is a Design Strategist with Design Concepts, translating organizational objectives into built environments. With a career founded in research, she is committing to understanding how our actions and interactions are influenced by the spaces we inhabit.

![[Case Study] Lessons from descaling 25 Scrum teams](https://www.agilealliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/descaling-teams-1200x630-1-150x150.jpg)

![[Case Study] Lessons from descaling 25 Scrum teams](https://www.agilealliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/descaling-teams-1200x630-1-300x158.jpg)