Most Agile coaches/Agile leads are hired in an organization to help address the dysfunctions that already exist. In my case, however, I joined a company that was already on a robust Agile journey. Healthy team dynamics and practices were the norms. My Scrum Master’s role was that of a servant leader, guiding and coaching teams and individuals to a more advanced level of agility, and the company witnessed delivery and results.

But all this changed when the company laid off the entire Agile lead team!

1. INTRODUCTION

In 2017 I was hired as an Agile lead in a Financial Services Company. It was exciting because my intention, at that time, was to learn and become more aware of the kind of change I wanted in my space. I also met a number of humans who created a great learning culture. In September of 2019, however, the company radically changed. Due to financial constraints, the organization cut down on some operational expenses. This led to the Agile lead team being laid off and that is what my story is focusing on—what happens when agile goes away?

In this report, I will share my story and relate it to much of what I sometimes see on social media where we coaches share frustrations or challenges with the organizations we work with. I will be focusing on my personal experience and lessons over a shift of mindset, delivery and most importantly psychological safety in terms of a SCARF model (Status, Certainty, Autonomy, Relatedness and Fairness) that was present in our working environment which was as much about collaborating as it was about my influence as a coach. While I am unable to disclose the Company name, I can share that it is a Financial Services company. The names of all the parties have been changed to protect their privacy.

2. Background

I had started out as a project manager before transitioning to becoming an Agile Team coach. Even though I had almost 5 years managing projects by the time I encountered Agile, nothing prepared me for the power and simplicity of Agile done well. I worked with the product and engineering team that was struggling in different ways to deliver value to our clients and I introduced Agile to the team as an experiment. While the team thought that Agile was more about practices, I also started coaching the team on shifting our mindset to focus on improvement rather than faster delivery.

I developed an experiential learning space that was consciously Agile first, with an appreciation that our problems are subject to the laws of the complex adaptive systems; change will be slow and successful practices will emerge. One lesson I learned from this experiment was not only did introducing Agile to the team make the team effective but also first, it exposed us to the problems we faced as a team. We had to take a step back and learn from our failures and how we could improve and that was the beginning of The Company’s Agile transformation journey.

In 2017 I decided to take a role at a Financial Services Company. I was there for 3 years. I was inspired to join this company based on what my role would be focusing on. At that time in my career I needed to get to a more advanced level. The Agile lead role was not only focusing on becoming a team coach but also improving organization agility by cultivating a learning organization.

This meant that as much as we were looking at things in a systematic way for product and engineering teams, we also needed to connect the rest of the organization’s culture and values to Agile principles. And these principles had to be coupled with the right mindset that involved high trust.

Our environment felt safe to collaborate; it was safe to act and safe to be and this encompassed aspects that leaned towards growth, learning and innovation. As Agile leads, we cultivated the ability to design interactions that minimised threat. For example, knowing that a lack of autonomy can activate a genuine threat response, it became a shared responsibility to consciously avoid situations that might enable a command and control leadership style. And knowing about the drivers that can activate a reward response that enabled people to be motivated, we could motivate others more effectively by tapping into their internal rewards.

I was privileged to work with a team of coaches who had a deep interest in practices, principles, and underlying theories that facilitated excellent team practices and products. This taught me how to model this to my teams. In their interactions with one another, I was aware of how they react to conflict, and could use non-violent communication, creating a safe space where individuals were able to give and receive feedback.

Organisational culture also played a big role in how we interacted with each other. The leadership team cared about hiring individuals who brought Agile thinking and diversity of perspective to their teams which meant that teams were trusted to create better outcomes for our customers. There was alignment and certainty in what we wanted to achieve as a company and how we connected the vision of the company to our codebase.

Along my journey with the Financial Services Company, I developed a deep insight into the level of challenges faced by the teams I worked with. They were motivated to have a disruptive mindset that was always willing to learn and experiment. This was one of the companies that are one of the best places I ever worked, until….

3. My Story Begins

September 1, 2019 started out as a normal Monday morning. There was something unusual about the energy but no one could put a finger on what was going on. Later on, at the company stand up, the CEO proceeded with the normal company updates but the end caught us by surprise! He started discussing challenges the company was facing like financial constraints and the tough decisions the board and the executive team had to make to ensure that they manage their monthly operational expenses. This included reviewing the structure of departments, as well as the number of resources in departments. And it meant cutting down on the number of people in teams. With silence in the room, including the people who had dialed in for the call, we were briefed that each team would receive a calendar invite to unpack the news and how it would impact the teams we work with. We went back to our work stations and kept on refreshing our emails for new updates. The only email that was important at that time was the Team Update because of the news that we had been given. While the engineering team was made up of software engineering, systems engineering, quality engineers and agile team coaches, the email was not sent to the entire team but to each sub group that made up the engineering team.

This was the beginning of the team no longer feeling whole; we were now in a different status based on our role.

The first group to receive email was the software engineering team. In their meeting they were informed that they were not impacted, but that some people who they worked closely with were. We had formed close relationships with some colleagues who were in this meeting so they were sending us chats on our phone when their update was going on. The groups that were impacted were the Agile leads and the quality engineers, but the engineering group was not told how we Agile leads were affected.

We Agile leads received an invite later that afternoon for a briefing. At that meeting the director of engineering, people team and the chief product officer told us that the whole entire Agile Lead team has been impacted and they had to let us go. They explained that this was a hard decision they had to make and some of us asked a few questions about the plan for teams we used to work with. We were informed that our role would be absorbed by the Tech lead or an “Agile champion” in the team. This kind of news about getting laid off was a scary, confusing time for me, which evoked self-doubt. Personally, I didn’t ask any questions in that meeting and I kept quiet the whole time because I was choked with my emotions.

That evening, we quickly formed a group and named it “The Best Team” and joined a call. We cried over the phone, we analyzed the whole thing, we tried to rationalize it, and we looked at what we did wrong and what others did wrong. We talked about our confusions. Maybe it was therapy, but we were all confused. We went through our most painful day together.

On the second day, I woke up with less grief. But I was still confused and trying to reason with what had happened. Everything before was way too normal. We got invited to individual consultations. As much as I didn’t want to face the new reality, I had to go to the office to begin my consultation process. The consultation sessions basically involved discussions around the notice period time, severance package, and an opportunity to ask any questions or provide any suggestions that could help in making the situation better.

Proposals that different teams sent to the management to see if they would be considered included salary cuts for everyone, ways they could still retain some people in the team, asking people to take vacations, etc.

It turned out that month was actually one of the toughest months in my life. I lost a loved one three days after getting laid off. Dealing with different kinds of grief the same week was heavy for me and the company was kind enough to provide psychosocial support for me. I wasn’t in the right headspace to make any kind of decisions although one knee jerk decision I made was to try and go for an interview a few days later after all this (I had reached out to my networks to organise an interview for me). During this interview I didn’t give my best because I was still angry. One could sense some level of bitterness in my speech and how I responded to questions. I decided to take some time off to process all the emotions and go through losses.

After a few weeks away I came back to work from my compassionate leave, and continued with my consultation process. During the consultation process most Agile leads opted to leave immediately, or after serving their notice period. One of my colleagues and my boss had drafted a proposal to management on how to transition teams to their new normal with acquiring some Agile skills and handing over some Agile lead work to the tech leads.

The proposal suggested that one Agile lead could remain behind with the intention of knowledge sharing and training teams in Agile fundamentals, facilitation and running any workshops that could be beneficial to non-engineering teams. They had me in mind, and I was given time to think about it and try to figure out how it would affect me. Ideally I was training my replacement in hindsight it seemed that they valued my work but they did not value me.

After a few days, I decided to take up the ‘new role’. I took up this new role as I was and still am passionate about nurturing an inter-dependent culture by enabling communication across different groups of people within the organisation. This placed me in a unique position to see how cultural coherence turned out in the company as a result of layoffs and how teams can be impacted when Agile goes away.

This allowed me to design ways to motivate myself. How can I be effective with the time proposed to change how teams interact and find new ways of working in just three months! There was some clarity on how long I would be staying. So I found a thrill in doing something I like even though I knew I was going to depart soon. I focused my attention on how I could increase autonomy during a time of uncertainty.

3.1 The next three months: Trust starts eroding

The transition started with redefining my role and how I needed to help with transitioning my role to others in the organisation. I started with having a session with my boss to gain clarity on the transition and how the handing over would look like in terms of knowledge sharing and coaching the team. We needed to set new expectations of my role.

3.2 Trying to honor the current old way of working

The first step was to look at what I had been doing and what kind of context teams had, especially some that I had not worked with and might need my help. Team dynamics were also different across the engineering team and non-engineering teams.

Before the change we had built a stable engineering team (which involved individuals and mission teams) with predictable familiarity and comfort. As much as sometimes teams were not comfortable with some of “the way things are,” we had developed familiar solutions to common problems. We had a relatively balancing system where individuals in the teams or the teams had a shared understanding that we were moving to more systems thinking and relate to a group rather than as individuals. Coaching them to be more self-organised was a process we had just started with the other Agile Team coaches before the layoffs. Teams knew what to do, how to do it, and understood where they fit in delivering value to our customers working in cross-functional teams. Teams also knew how to get away with some behaviours that were not desirable. An example before the whole layoff, teams felt safe to support low performing members by everyone else doing a little bit extra or tolerating a dysfunctional behavior and nobody saying anything about it. I will explore more how this kind of safety was impacted and how we moved from a team supporting each other’s culture to individuals pointing fingers at each other when something wrong is done.

We needed to create a shared understanding and create some expectations in terms of my role and how to run team sessions. In my first sessions with teams I did not facilitate meetings. Instead I asked for a volunteer to help in running a session that I would observe and see how I could help. I would then share feedback with the team on my observations that were based on what I thought were the most important things that needed to be improved and how they saw my role during that improvement process. As so many things were being brought to my attention and different teams were asking for help, I had to keep reminding myself that I was in a space where it feels uncertain and unpredictable and I can’t always know what comes my way and can’t always have the answers. Preparing myself for this kind of disruption enabled me to be comfortable in saying “I don’t know” or just saying “No” when I was not able to help a team with something.

3.3 The cracks start showing

During the 30 days notice period for Agile coaches, teams were also impacted by the resignation of almost all Quality engineers in their teams. This required them to respond by ensuring that quality was now going to be a team responsibility and having to organise how to run and test software on their own. This change caused individuals in the team to be more aware of the Quality engineers’ opinions and feedback counted the most in how they were doing their work. So we were faced with a crucial issue of testing as well.

This brought a level of instability in how work was being delivered and our definition of done. Teams did not care about quality as much as they should but rather, focused on how fast we delivered work. They avoided issues that were arising in our systems or blaming someone for causing the issues we were facing. Teams came up with a strategy of reviewing each other’s work. But the challenge was they didn’t know what to look out for and approved work for the sake of completing the work. Another challenge we faced was that the new way of communication that was more focused on speed, pressure on deadlines and not quality; individuals in the team didn’t get time to review each other’s work so they opted for everyone to test their own work and push it to done which created individual silos and isolation.

This kind of resistance where no one wanted to take ownership of improving agility blocked our awareness of issues that were arising within the teams and our work.

3.4 Then this happened

While finding ways to help teams, two and a half months after I got back from my leave, we went through a rather chaotic phase where the members in a team kept shrinking. Teams had to be merged and this required some team kick off sessions. New engineers were joining the company, and individuals who had never worked together, because of the radical changes, now needed to.

After two kickoff sessions, engineers started resigning and the new teams were now also shrinking. Kickoff sessions were no longer sustainable. This triggered a threat in the form of anxiety and vulnerability. The remaining engineers lost their ability to concentrate for much of the day and this impacted what teams committed to at the beginning of an iteration. It was such a chaotic time that people were desperately looking for new hope and this led to individuals applying for jobs unashamedly during working hours. The productivity in teams and quality of work took a nosedive!

4. Rising Away From the Chaos: Building Relationships

To better understand and empathize with the organisation’s needs, I needed to spend more time with certain Tech leads and stakeholders of different teams. We scheduled several meetings (almost weekly) with Tech Leads, POs and some business stakeholders. These conversations helped me better understand the true frustrations they had with what was happening in the organisation. I attended status meetings where I knew the stakeholders would be present; and it became apparent to me that the silos and pressure of delivering fast had caused a great deal of miscommunication about how teams were currently working. The business team thought the development team’s focus was as normal and nothing should have affected them. This was completely different than what it really was. The truth was being lost in translation—a game of telephone was going on between the Tech leads and the business team when Tech leads would communicate commitments on behalf of the team and make promises of deliverables. My presence in these meetings and openness about what was happening at the team, constellation and management level acted as an opportunity to build relationships with the Tech leads that would be based on transparency and reestablishing trust that was lost within the teams.

During this time Tech leads were now becoming more aware that we were not operating business as usual. They understood that there’s no kind of a magical solution that would help if we attempted to short-circuit this wave of disruptions and emotions that affected the performance of the team. All these kinds of emotions were valid and I had to address them because I was also going through the same kind of emotions. Even when I had the best intentions, I needed to allow myself to understand that I was not in a position to fix the problem because emotions are too ingrained; they belong to their owners. Still I had to coach those who welcomed my help to manage the transition from emotion to behaviour, because they needed to function effectively on the team.

Over the following weeks, the Tech leads recognised that miscommunication was affecting the business and realised that the kind of transformation that needed to happen had to start from within. We needed to improve trust because the team exhibited behaviours that related to dysfunctions in a team—absence of trust, fear of conflict due to inattention to results, and lack of commitment. I needed everyone on the team to feel that they could trust the tech leads and one another as well so that their contributions mattered.

4.1 Building understanding before making changes

Having conversations with the Tech leads for one team, I allowed them to define their expectations and goals of what they would like to work within the new normal. These goals could later be used to guide what practices might be taught and coached within the rest of the team. The purpose of these conversations was to create an awareness of what was going on and to have a common shared understanding.

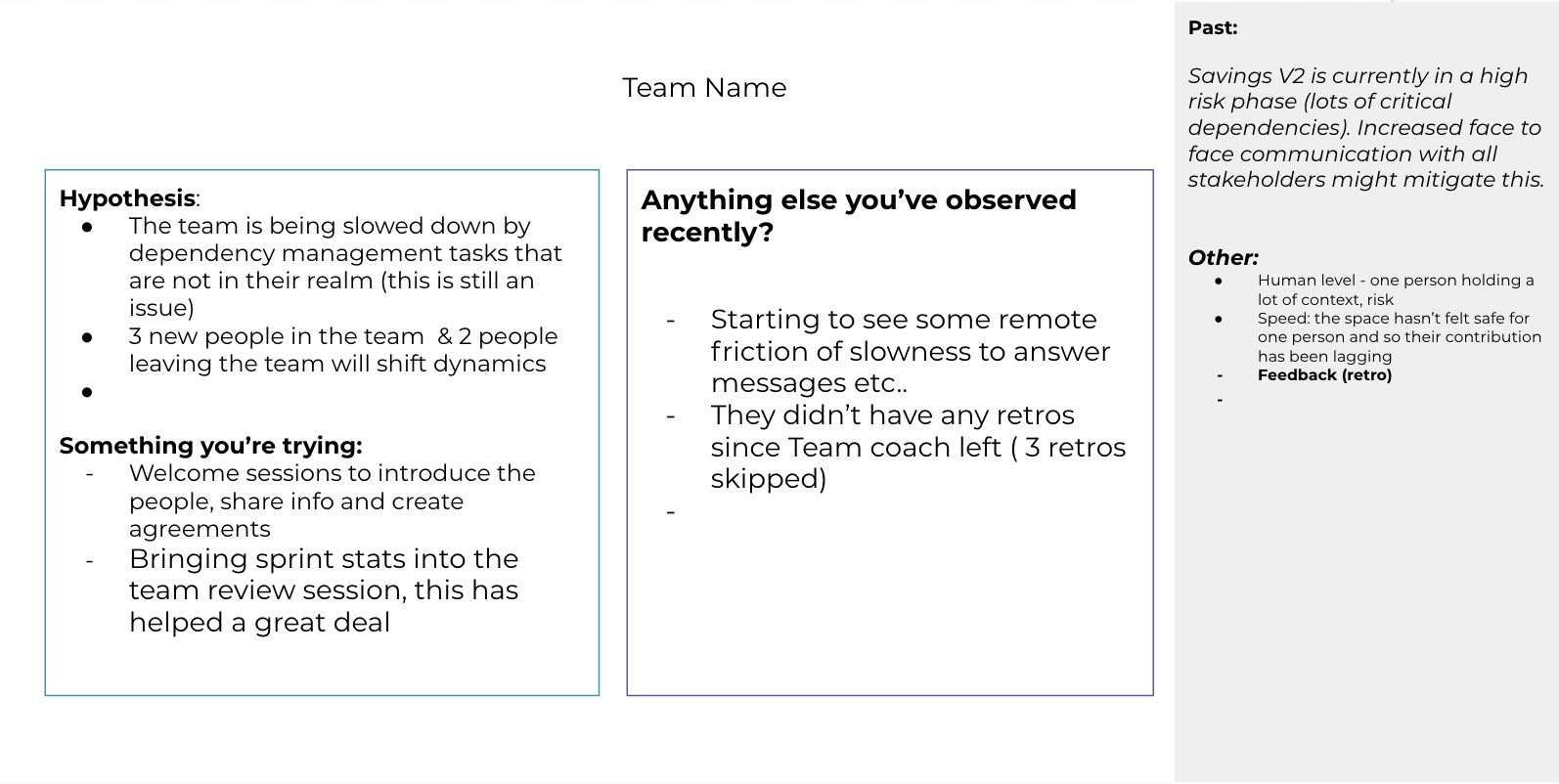

The Tech leads and I needed a structure and communications tool for coordinating our efforts that would help us to drive actions and behaviours around experiments. The hope for this structure was that it would help us have a more holistic approach which goes beyond a single team but also work for the entire engineering team and non-engineering team. It tries to mirror the challenges, behaviours and constraints that I was experiencing with the teams during this time. Most times addressing challenges meant exposing issues, visualising them, questioning a solution, or directing and stimulating the identification of alternatives and options. I tried building a structure that focused on values and principles of the Agile Manifesto:

- Identify through observation behaviours which are not supportive of an agile mindset

- Formulate hypothesis about the reasons why these behaviours are manifesting themselves given our context

- Define a Goal, as a behavioural improvement that we want the team to achieve

- Define Metrics that will allow to measure the effects of the coaching

I centered on one particular team that had just been merged. We clarified outcomes with the Tech lead and team members. Initial conversations were about re-establishing trust, getting back to having retrospectives, having realistic sprint goals, and defining metrics that would be valuable in making decisions. The product stakeholders and the team were all frustrated that nothing had gone to production yet despite the changes that had occurred within the organisation. The Product Owner was struggling to make the team release when possible and having an environment to share this feedback with the team as they were still at the storming stage. So I focused on finding a way for the team to visualise the work they were doing by creating a simple dashboard to visualise the results. Below is an example of the structure we used for a particular situation:

Figure 1: Visualizing Our Hypothesis, Observations, Past Behaviours and Proposed Actions

Figure 1: Visualizing Our Hypothesis, Observations, Past Behaviours and Proposed Actions

Sensing that other teams across were experiencing meetings without clear outcomes and unclear goals, I facilitated a workshop with the Nairobi team on facilitation foundations. The first half of the workshop had the teams post on the wall how they would want meetings to feel like. We then went through the facilitation framework that would help them understand meetings aren’t just about what happens while at the meeting. We also looked at the Meeting cycle and how to deal with dysfunction behaviours that act as a substitute for expressing displeasure with something in the meeting the participant does not agree with (i.e. content, process, other participant’s opinions, or outside issues).

Trying out these few things with teams and seeing individuals in the team being Agile champions really gave me hope and I felt proud of myself. As a team coach I had had the best intentions. But as much as I can be a change agent I couldn’t change the overarching challenges caused by a massive culture shift. Yet I was happy when I saw teams starting to use some tools for change in their teams. This reminded me why we as team coaches believe that people are creative, resourceful and complete when you believe in them and coach them to become better at what they do.

5. Conclusions

Change is difficult and confronting. But validating the changes that took place during the transition with small safe-to-fail experiments, executed at regular intervals, reduced resistance in teams. As I mentioned earlier, my story does not have a happy ending. Transforming the chaos and going back to the good old way of working was what the organisation hoped for. But staying behind for three months opened my eyes to what can go wrong when an organisation weaponizes psychological safety. It also opened doors of opportunities.

I asked one of the senior engineer of his impression of what it felt like when Agile went away and here’s what he said:

“The phrases “waterfall with a crunchy Agile shell,” “Agile in name only” and “a stalled Agile journey” best describe the post-2019 restructure environment that we suddenly found ourselves in.

Up until September 2019, what had been an exciting Agile journey, had paid dividends by way of an incredibly transformative impact in the dynamics of how we organized, worked and interacted. There was a robust culture anchored in trust, respect, tolerance, blameless introspection and feedback, empathy and diversity among many other admirable qualities born out of it. More importantly, there was a sense of ownership and responsibility that was a direct result of this Agile journey being a concerted effort between teams, agile coaches/leads and both engineering and the wider company leadership.

As individuals and as a team, we had come to understand that Agile isn’t a methodology. Treating it as one confuses process with philosophy and culture, and that’s a one-way ticket back into Waterfall—or worse. And that’s the ticket, unfortunately, that the company had booked. With such noticeable signs as sudden obsession with metrics, comparing velocities of teams and individuals, story points and deadlines being treated as goals, everything and anything becoming a priority or urgent or an urgent priority, stand-ups that grew longer by the day, lack of retros without any of us giving a care in the world, it was obvious that we were in a different era. An era heralded by the departure of agile coaches. Worse still, the endearing culture that we had all worked hard towards wore off little by little. And just like nature, culture abhors a vacuum.”

Looking back, these transitions had an impact on what I felt was safe before and after the change. After the lay off news, personally I gained a perceived loss of status; and this happened with teams as well. We became more of a working group than a team that trusts each other. For those three months after the layoffs, the only certainty was the date of my last day of being officially employed by this organisation. How are the teams going to work without an agile lead, what would my future hold? A great deal of uncertainty.

Teams previously were used to having the opportunity to make decisions. But this was no longer available with the new normal. They now had to embrace changes without asking questions. The interesting thing that happened with how people related with each other after the change was that people in different teams and departments reached out to us Agile coaches to offer support and kind words. So many things changed but I am glad that people kept the culture of how they need to relate with each other. Fairness is largely based on perception. Based on my perception, laying off agile coaches was not fair and no one could make sense of why our role was impacted.

From my experience those who speak of Agile are predominantly speaking about the theory of constraints that identify the most limiting factor that can stand in the way achieving a goal and then systematically improving that constraint until it is no longer the limiting factor. But as with manicured gardens, without maintenance and nurturing they atrophy. While they were many small lessons that I learned, the three that stood out most from my experience were:

- Psychological Safety is not a luxury for Agile teams; it’s a necessity. During the transition period I witnessed many situations where people felt psychologically unsafe and I was aware of the impact it had on team delivery. The Use of the Scarf Model helped me in making observations and mirror the information to the leadership team and teams as well as to understand the before and after of our way of working. The lesson learned during the transition was that when trying to instill a culture of psychological safety that was already there in an unsafe environment that is threatening, waiting for the most opportune moment can have unexpected consequences.

- Organization culture exists and its manifestation is in the form of behaviours habits, parables, sacred stories and failure stories that are created by humans. This can change. By making these explicit, awareness will increase and coherence will emerge. While we can’t design the culture we want, we can influence it and encourage certain behaviours by making this explicit with team kick off meetings and making what is implicit visible.

- The transition period influenced the next chapter of my life. Ultimately getting laid off was one of the best things that happened to me. My experience at the Financial Services Company helped me tune my Agile BS detector when in interviews and gave me things to keep on my radar. There’s a lot of information out there—some good, some bad. It can be difficult to distinguish one from another. This experience gave me practice spotting dysfunction. It helps me identify whether a potential employer will be the right place for me, and helped shape my mindset. It’s a lens I still use today. A hard truth I had to learn was no matter how much blood, sweat, and tears you put into an organisation, it will still go on without you. I became a Scrum Master because it’s something I enjoy, and I wanted to be good at it. I changed my perspective. Commit yourself to a learning journey and not to a job. You have to do what’s right for you.

6. Acknowledgements

I would like to thank a lady who I am privileged to call my mentor and a friend, Cara Turner, who encouraged me to share my story. To the best team! Kirst, Jay, Bee, Willy and Maureen working with you was such an honor, I learnt a lot from you and am thankful for the support that we have always shown each other throughout.

Finally, I’d like to give a huge thank you to Alex Kanaan and Rebecca Wirfs-Brock, my shepherds throughout this writing process, for their patience, kind words and clear, concise feedback. This paper would not have come together without their assistance.

REFERENCES

[Rock] D. SCARF, a brain-based model for collaborating with and influencing others.

http://web.archive.org/web/20100705024057/http://www.your-brain-at-work.com/files/NLJ_SCARFUS.pdf