I have been a scrum master for three years at a food-tech startup in South Korea, one of the most competitive markets in the world. Since then, the company has grown explosively through mergers and acquisitions. Our tech organization has faced drastic changes in the way we work and in our culture. I hope you will taste the real-world practices of the scaling up at a startup and see how our tech organization has evolved at each stage of our journey.

1. INTRODUCTION

Our scale-up Journey was a roller-coaster ride, Scrum to Waterfall to Agile.

Making a transition from startup to scale-up is a process of survival. We went through rapid growth and at every moment, we faced new challenges. Especially in the tech organization, fundamental development principles and culture were disrupted as our company grew. It could be natural progress to scale-up, but nobody wants to lose the values that they had in the beginning. This report is a story about how we transformed for growth and tried to define our way of working, the RGP way.

2. Background

In 2015, our company was providing online food delivery service with a product, Yogiyo. At that time, we had self-organized (no managers) dev teams using Scrum and they voluntarily assigned tasks for each sprint. However, as business was growing faster and competition became extremely fierce in the market, hundreds of backlogs were created every week, and it caused chaos of prioritization, decreasing velocity of dev teams. I will describe how scrum masters worked with dev teams to overcome this challenging situation helping team members to collaborate effectively with business stakeholders and executive management.

3. STAGE 1: A SINGLE PRODUCT, SMALL TEAMS USING SCRUM

Many startups adopt Agile in their early stage and expect to maintain business agility as they scale up. Our tech organization used Scrum from the get-go, and it looked like we had solid practices. Two dev teams were running two-week sprints respectively, doing almost all Scrum ceremonies (e.g., daily stand-up, sprint planning, estimation, release planning and retrospective) within a flat organizational culture. Despite these benefits, a conflict was generated between dev and business (e.g., marketing, sales, and operations) teams as the company grew.

3.1 Problems

- Autonomy vs. business priority.

- Scrum myths and misconceptions in dev teams.

- Undefined product owner’s roles and responsibilities.

The dev teams had a confrontation with business teams because they thought that business stakeholders always pushed them to meet a deadline for product delivery. For example, our marketing team requested the dev teams to deploy a promotion page by a specific date and said it was very urgent. From marketing team’s perspective, it was natural to know when their request could be completed so that they could announce the event schedule to customers in time.

On the other hand, from the dev team’s standpoint, it was an unreasonable request since they already had a fixed sprint backlog and believed that it should not be changed as possible for following reasons.

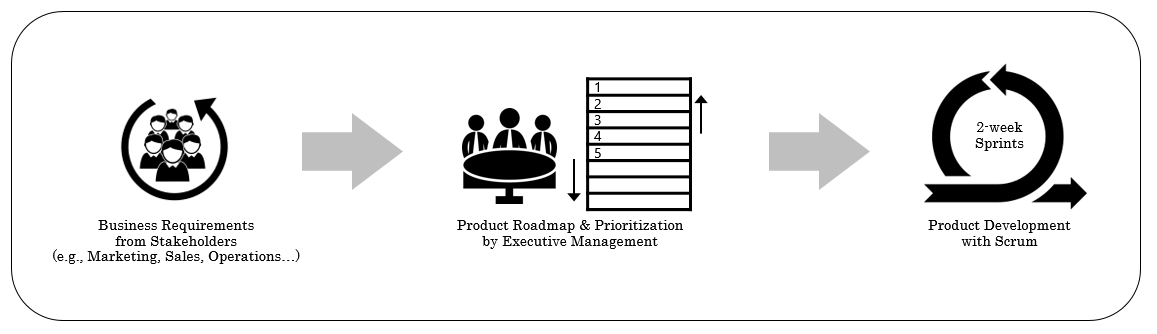

Firstly, business priority was already reviewed and decided (see Figure 1) in the process of sprint planning. So, if the request was significant, it had to be shared and discussed before starting a new sprint.

Secondly, the dev teams believed that a deadline-driven approach such as Waterfall was “wrong” and they should be rejected. As a result, a deadline has no meaning for the dev teams because they would deliver features during a sprint, and this was what they thought “right” about Scrum.

Lastly, backlogs created by the marketing team were mostly business requirements without functional specifications that resulted in dev teams not being able to estimate stories accurately due to lack of information. It is because there was no dedicated product owner who could analyze and refine the marketing team’s requirements and make dev teams understand the required features. As the same problem was often repeated, dev teams became conservative about changes during a sprint, especially receiving incomplete backlogs.

Figure 1. How we prioritize business requirements and put them into sprints

Figure 1. How we prioritize business requirements and put them into sprints

3.2 What we did

- Collect feedback through a retrospective and identify dev teams’ expectations.

- Scrum master with a role of “cross-link” [1].

- Backlog refinement before estimation.

- Hold a development process introduction session for business stakeholders.

- Monitor feedback through retrospective to measure the effectiveness.

Through a retrospective meeting, we all agreed that we needed a person who could take the responsibility to resolve these challenges by fostering cross-team collaboration, and believed that a scrum master could take that job. I understood our dev teams’ key expectation for scrum master and thought that being a cross-link was the best way to deliver value to the organization.

As a follow-up action, scrum masters started to review product backlogs which were created by marketing, sales, and operations teams. A guidance was given to these teams to refine their functional specifications so that our dev teams could estimate each backlog accurately. Sometimes, stakeholders were invited in the estimation meeting and they gave detailed explanation of their request directly to dev teams. This way, both stakeholders and dev teams could efficiently interact each other through face to face communication.

Also, training sessions were conducted to introduce our development process for business stakeholders, especially when newcomers joined the company. It was a good start for them to know dev team’s basic workflow and how we collaborate.

Finally, we continuously monitored feedback from both parties (e.g., dev teams and stakeholders). Internally, we could review our improvements related to cross-team communication in the retrospective meeting and discuss what further actions would be necessary for better collaboration.

3.3 Conclusions

- Understand each team’s key expectations for Scrum framework.

- Define the role of scrum master based on organizational context.

- Deliver value for effective cross-team communication.

In Stage 1, our key finding was that each team had different conceptions about Scrum. For example, the dev teams valued most on autonomy, but they were too much obsessed with Scrum rules. On the other hand, business stakeholders believed that Scrum could accelerate product time to market, but they could not forecast appropriately when their request would be done and deliver value to customers.

To break through these challenges, we defined the role of scrum master as a dedicated coordinator to boost cross-team communication. As a result, both parties could gain a better understanding of mutual needs and how Scrum practices and scrum masters could efficiently support them.

4. STAGE 2: GROWING THROUGH MERGERS, INTEGRATING DEVELOPMENT CULTURE

After several mergers, we had challenges and difficulties, especially operating our two best-known products, Yogiyo(YGY) and Baedaltong(BDT) in the same marketplace. After the merger of BDT, the size of our tech organization almost doubled, but it was pretty clear that it would take time for BDT teams to adapt to changes in our overall product development processes and cultures. YGY dev teams used Scrum, and BDT dev teams used Waterfall. What approach would you take if you had to integrate dev teams having different work principles and frameworks?

4.1 Problems that we encountered

- Lack of knowledge sharing between YGY and BDT teams.

- BDT’s Scrum adoption failed due to insufficient training opportunities and organizational support.

- Cultural stress resulting from a radical restructure from a flat to a hierarchical organization.

- No continuing executive support for Scrum.

- Lack of organizational consensus on how we can work better together.

In the beginning, the CTO decided to adopt Scrum for newly joined BDT teams since existing YGY teams had a very strong objection to Waterfall. From the YGY teams’ perspective, Waterfall was the way to push them to do overtime work to meet the deadlines. Because of the significant cultural differences, it was hard to create chemistry between YGY and BDT teams. That lack of chemistry became a barrier to knowledge sharing.

BDT teams also had hard times in the new environment, and they needed to warm up because most team members didn’t have Scrum experience. So, we set up a BDT development workflow first, applying the same processes used by YGY. Then, we tried to apply some basic Scrum practices (e.g., daily stand-up, creating a backlog, estimation using story points) gradually. The piecemeal approach to Scrum didn’t work because we didn’t train the BDT teams, and they failed to fully adopt Scrum. There were only two scrum masters who served the two YGY teams (the Red and Yellow team, respectively), and we didn’t have enough scrum masters to support the BDT teams.

Moreover, our organizational structure rapidly changed hierarchically as the company grew. In the end, Scrum didn’t work well at all since the senior management started to focus on project deadlines. For example, the executive management discussed business priorities, planned product roadmaps and initiated projects which had to be released by specific due dates. Waterfall dominated our tech culture, and BDT teams lost their opportunity to learn Scrum and Agile culture.

YGY teams faced tough situations, too. They felt frustrated because they thought that something went wrong when they saw a traditional WBS (Work Breakdown Structure) for a project. Many developers were disappointed that our tech organization had lost its original values and culture – small, autonomous, flat teams.

Lastly, scrum master’s duties and role also changed to project leader to process optimization facilitator corresponding to organizational restructuring. We should have been flexible to work in the changing environment, believing that we could learn through experience. However, it was hard to make other people clearly understand a scrum master’s role.

4.2 What we did

- Defined OKRs to cultivate tech culture.

- Define scrum master as the facilitator of practice, communication, and collaboration.

- Encouraged all dev teams to do a retrospective meeting regularly.

- Reviewed and refined our overall development practices.

- Set up consistent work principles in the tech organization.

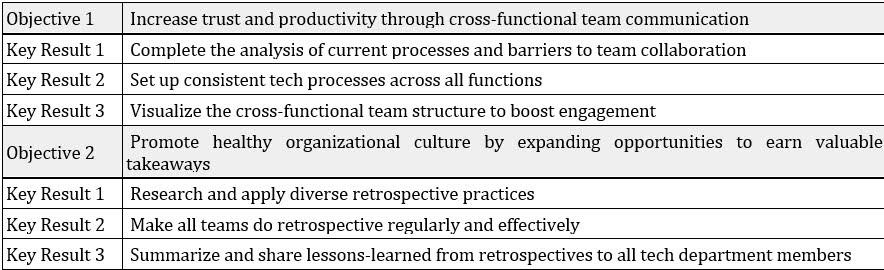

A new change started from new leadership. Our company rebuilt the executive leadership team bringing in new people based on substantial experiences in organizational management who could redefine the way we work at scale. To initiate a bottom up change, our team set up the OKRs (see Table 1), and our top priority was to rebuild our tech culture. From this moment on, my duty was as a facilitator to encourage employee feedback through the team retrospective, improve development practices, and boost collaboration in the tech department.

Table 1. 2017 Q4 OKRs – scrum master team, tech department

Table 1. 2017 Q4 OKRs – scrum master team, tech department

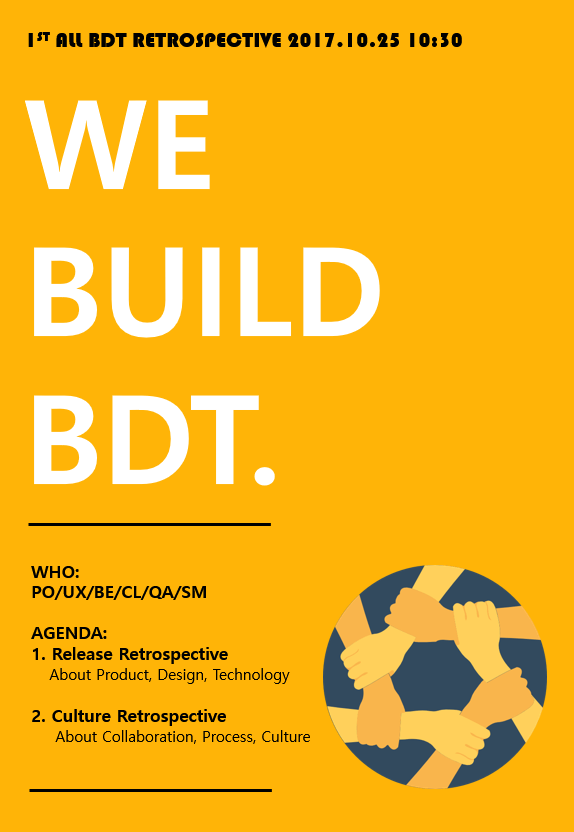

Even though we suffered significant growing pains through mergers, team retrospectives and daily stand-up meetings remained one of our solid practices and became a powerful tool for cultural integration between YGY and BDT teams. At this time, I was a dedicated scrum master for BDT teams, so I could share our values on how these practices help communicate effectively, not only for functional teams, but also for cross-functional teams (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Retrospective practices of the BDT teams

Figure 2. Retrospective practices of the BDT teams

We started a retrospective meeting at a functional team level. After that, we expanded it to a retrospective at a cross-functional team level because we discovered some broken processes between functional teams and the teams could not fix them alone.

For example, we found that it was unclear when UX designers should start Design QA in the existing process. We conducted an App release retrospective meeting after a new version update of the BDT product so that all members —product owners, UX designers, backend/Android/iOS developers, QAs—could look back on the recent release, and discussed when and where we had encountered obstacles, suffered miscommunication and needed improvements. As a facilitator, I helped them to talk about what should be improved based on the release workflow. All members shared feedback and suggested ideas how we could collaborate better regarding Design QA and fix the process. As a result, we learned how to communicate efficiently, improve our practices, and build mutual trust through the retrospective.

Regarding the organizational structure, we restructured product-based teams to skill set-based groups. As a result, we had a backend chapter, client (Android/iOS/web), QA teams and no more YGY/BDT divide. Then, scrum masters supported each dev team to set up a team Kanban. We chose Kanban as a basic framework for dev teams because of the following case study.

A backend team wanted to adopt Scrum, but they could not see the burndown chart actually burned down since they were working with multiple product owners for various projects. It caused frequent scope changes during a sprint, and the backend team realized later their practice was wrong. In the beginning, they thought that Scrum didn’t work well because of low performance. However, in reality, a new approach was necessary for them to realize how to use Scrum or other Agile practices efficiently in the scaled organization. Our tech department found the new way of working which was suitable for its scale. As a scrum master, I learned how Agile practices and culture transformed in the growing organization and influenced teams to move forward to the next level. Also, I learned that a scrum master’s role could be broader and transitioned to serve a large organization.

4.3 Stage 2 Conclusions

In Stage 2, we learned how our tech organization suffered culture clash after mergers, and we began our journey to rebuild processes and trust. From these experiences, I strongly recommend that you define a cultural integration strategy that you’re trying to build at the very beginning. We put three years of effort into overcoming a cultural divide, though we still have a few difficulties. Despite the challenges, we had confidence that a retrospective was a powerful tool for boosting communication and cultivating a collaborative culture in the organization.

5. STAGE 3: SQUADS – ADOPTING AGILE AT SCALE

In 2017, our company scaled-up to more than 400 employees, 60 teams, and 7 departments. We had an R&D Center which consisted of product and tech departments for product development. Although these functional organizations were created to deliver YGY & BDT service, we had emerging concerns due to different work styles. So, we considered for ways to better move towards a common goal and introduced virtual organizations called Squads modeled after Spotify’s framework for scaling Agile. A squad is a full-stack team with all skill sets necessary for product development. Whereas a functional team moves based on the team’s KPIs or goals, a squad works together under a common goal aligned with the product.

5.1 Existing problems we had when introducing Squads

- Lack of building trust between product owners and developers.

- A deadline-driven approach triggered conflicts in the squad.

- Project scopes got bigger and project timeline prolonged up to 3-6 months.

- Deliverables sometimes went wrong and did not meet the project objectives.

In the beginning, there were 10 squads, and we appointed a squad leader for each one to stabilize the new type of organization. Each squad could decide their own way to work together. Our initial purpose was to foster autonomous cross-functional teams by providing a minimum framework and fewer processes. Contrary to expectations, some squads were confused about role setting and communication. For example, which issues or risks during a project should be escalated to the executive management and who should take responsibility for reporting. Since each squad member had a diverse background and experiences, they had different standards and expectations about teamwork.

One of our significant conflicts was that a product owner and developers in the same squad often disagreed with each other. First, they did not feel they were a “team” psychologically, yet. A squad was a virtual organization; each individual still belonged in a different department and worked with different executive management (e.g., the product and the tech department, respectively). Second, they had a different approach about project estimation.

In most cases, a product owner asked a fixed deadline to developers regarding the development schedule in the early stage of a project. Developers thought that it was an unreasonable approach because they could not estimate the project scope accurately due to unclear spec documentation. Moreover, frequent scope changes during the project were not only making it challenging for developers to predict the target release date, but also affecting deliverables. For example, squad members put in time and effort over 3-6 months, but they found that they had missed some features at the last minute just ahead of release, or made a wrong product which was not aligned with the stakeholder’s original purpose. The principal argument between a product owner and developers resulted in low productivity, disharmony, and made it hard for the squad to get things done.

In summary, we introduced the Squads as our new way of working, but the fact was that some members still maintained their attitude they used to be in the functional organization, and our initial approach that each squad may set up its own ground rules was not enough to change a squad to a highly collaborative team.

5.2 What we did

- Set up squad weekly progress meeting: squad leaders could escalate issues and cross-check potential dependencies among squad.s

- Strong leadership initiative for change: the CTO officially announced Agile adoption for squads.

- Transformed local discoveries into global improvements[2]: we chose a pilot squad for Agile transformation and made a best practice case which could apply for other squads. (e.g., minimum viable product, combine Scrum & Kanban, sprint review).

- An independent team space for a pilot squad: we made squad members sit together to encourage a team spirit.

From the first quarter of 2018, we started our journey to transform squads to highly collaborative teams. First, we clarified a squad leader’s duty and let them escalate issues directly to the executive management in the squad weekly meeting. This way, we could improve transparency of information regarding squad progress, and decrease communication complexity by shortening formal reporting lines in the matrix organization.

Second, we decided to use Agile as our fundamental development method for squads. A strong initiative for change began from the CTO to rebuild the way we work and improve productivity of squads. But we needed proven best practice examples for the whole transformation because it was difficult to form an organizational consensus for Agile.

In February 2018, the new billing system project was selected as a pilot squad for adopting Agile, and the CTO decided to assign a dedicated scrum master to the squad. This squad originally initiated in November 2017, but the squad members suffered delays and conflicts. While the project scope was big, the developers were pushed to meet the unreasonable deadline without a detailed discussion. So, the squad needed a turning point to move forward, and we transformed the squad to a Scrum team. We had seven members, a product owner, four developers (e.g., backend, API, web), a QA and a scrum master. Since most members were new to Scrum, our first action was to hold a workshop so that squad members could gain a basic understanding of Scrum. As a scrum master, it was a unique learning opportunity for me that we could start from scratch because billing system was a traditional area and developing such system using Scrum was our new challenge.

Define an MVP (Minimum Viable Product) as a shared goal

We defined an MVP that consisted of three milestones, and created backlogs corresponding to each milestone. Also, we shared our goal and the scope of MVP to stakeholders clearly so that everyone could have the same understanding. Since our squad and stakeholders set up a shared goal, we could keep focus on essential features of MVP, preventing potential impediments from secondary feature requests.

Daily stand-up to build a strong team spirit

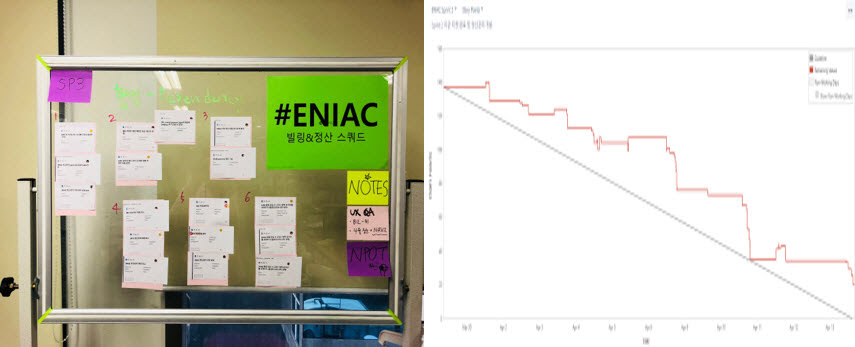

We set up our ground rules for team communication based on Scrum ceremony. Daily stand-up was the key ritual to encourage our teambuilding and collaboration. Since our squad members could sit together in the exclusive space, we could have a daily stand-up meeting there. It was a perfect environment for team communication. For example, we found that mutual dependencies and queues between developers were a blocker in the sprint 2. So, we started to use visual aids (see Figure 3) in the daily stand-up to relieve co-work dependencies. This way, each developer could check the progress of related tasks according to their priority. As a result, productivity improved and the sprint 3 burndown chart showed decreased lead time after applying this practice.

Figure 3. The new billing system sprint 3: (Left) Dependency check board (Right) Burndown chart

Figure 3. The new billing system sprint 3: (Left) Dependency check board (Right) Burndown chart

Combine Scrum & Kanban

Starting at the end of February, our squad began to implement sprint 1-4, and it took a total of 9 weeks to complete the MVP. After finishing the sprint 4, we decided to switch from Scrum to Kanban because it was more suitable for usability testing in the production environment cooperating with stakeholders (e.g., finance department). While Scrum was a great tool for building an MVP with a tie-up cooperation of squad members, Kanban was useful for stabilizing the product and improving quality because it was more flexible than Scrum when we needed to reflect stakeholders’ feedback and priority before the official launch date.

Review with stakeholders

We had a sprint review meeting after completing every sprint, and invited stakeholders when we had to demonstrate major features. It was helpful for both the squad and stakeholders because all people could confirm that we were on the same page. Also, both parties could share progress based on the product (e.g., the working software), so we could sync the common objective and check that deliverables met the needs as expected before release.

Agenda for sprint review:

– Sprint summary (by scrum master)

– Things to demonstrate (by product owner or team)

– Issues & feedback (by team & stakeholders)

– What’s next? (by product owner)

5.3 Stage 3 Conclusions

In Stage 3, we explained why and how we initiated the Squads, and introduced our new experimentation, adopting Agile for billing system development. We learned that Agile could be a strong tool not only for product development, but also for building a highly collaborative team.

- Transition to the self-organized team was demanding and required a certain level of leadership, ownership and a mature mindset for all squad members.

- Strong leadership was essential to drive change at a scaled organization.

- Starting an Agile transformation from a small team: we chose a pilot squad that needed a new approach to resolving delays and conflicts. We could successfully change the squad to a Scrum team and achieve our goal because Agile provided new learnings to the squad and the members were open-minded for a new challenge.

- You don’t have to choose either Scrum or Kanban, you can do both! We recommend to use a right method depending on your team and project characteristics.

- Use Agile practices for all. A sprint review was a beneficial way to cooperate with stakeholders.

- Making a change on an organizational scale can be slow, but the most important thing is to make continuous progress, leading by example. Agile transformation is a long-term journey.

6. What we learned

- Working at a startup means that you will always face challenges. So, it is highly essential to adapt to the rapidly changing environment and have a growth mindset.

- To integrate two different cultures after a merger, we strongly recommend that you define the cultural integration strategies for the culture you’re trying to build at the very beginning. Otherwise, it might be too late.

- In growing organization, strong leadership initiative would be a start point to build a consistent working culture.

- Increasing employee engagement is the key to organizational health at every level. A retrospective is a powerful tool for boosting communication and cultivating “we” culture in the organization.

- Last but not least, a scrum master’s roles and responsibilities at a startup can evolve from being a facilitator to an Agile coach according to organizational growth and continually changing environments. Sometimes, this might be confusing when it comes to making other people understand clearly your role. From our experience, we would like to suggest that being open-minded and trying to shape your core capabilities were the valuable takeaway when working at a startup.

7. Acknowledgements

We sincerely appreciate having been able to participate in Agile 2018 journey as authors of this experience report. Thank you to the track chairs, Rebecca Wirfs-Brock & Sue Burk, for reviewing and accepting our session proposal and for giving us this precious opportunity. We want to thank our shepherd, Johanna Rothman, she is a great mentor with a warm-heart. We could not have completed this report without her guidance, and we have learned a new approach and practices for writing a report. Also, we want to thank our colleagues who joined us on our Agile journey together.

REFERENCES

1 Johanna Rothman, “Organizing your agile teams? Think autonomy, mastery, purpose” https://techbeacon.com/how-best-organize-agile-teams-build-around-autonomy-mastery-purpose

2 Gene Kim, Jez Humble, Patrick Debois, and John Allspaw “The DevOps Handbook: How to Create World-Class Agility, Reliability, and Security in Technology Organizations”, IT Revolution Press, 2016, p.42