Clear expectations on what to expect from the Product Owner (PO), Scrum Master (SM) and IT managers are key for an effective collaboration. Derk-Jan shares his experience and gives practical tips to on how to align expectations in a scaled multiple team organization where every team and manager has their own opinion.

1. INTRODUCTION

Many agile teams and organizations are struggling with executing the various roles in an appropriate way. Scrum Masters that book the meeting rooms but fail to challenge the team. IT managers that control the team rather than facilitating them. Product Owners that lack the power to really own their product and say no to demanding stakeholders. The examples are countless. During my coaching I always focus on getting the roles clear. In this report I will share my efforts to get role agreement in larger multiple team organization, where management is in a transition from traditional management toward agile leadership. Where opinions and maturity vary from team to team and exceptions rule.

2. Role Agreement in small organisations

I have guided several organizations that were quite new to agile and had a small IT department. In some organizations I was the only agile coach, which gave me a unique position. It made me a single source of truth as it comes to agile practices. Many times, the advice I gave on the role of the Product Owner and the Scrum Master was accepted without much debate.

2.1 The CEO: “I will tell the stakeholder that I asked for the PO to say no”

One organization I worked for had trouble with completing their work. I gathered the business stakeholders to discuss the production deployments. I wanted to know how the last deployment towards production had gone, what process was followed and what problems they had encountered. One of the business managers, she was from marketing, started to frown. “I don’t think we got anything towards production this year,” she stated shamefully. Fact was that the team was approached by everyone for everything and was not able to work on items long enough to decently finish anything. Predictability was low, as was the image of the IT department.

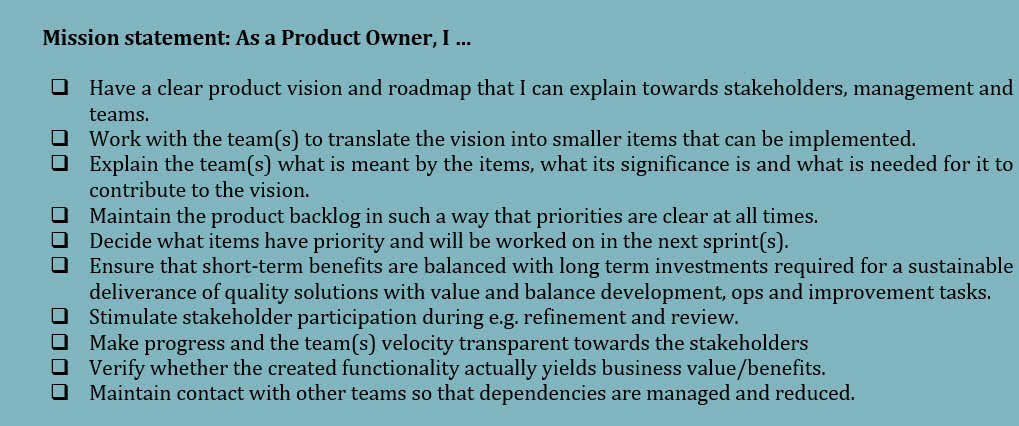

I sat down with the Product Owner to see how we could improve this. He shared what he did, and it became clear that he spent most of his time executing administrative tasks in the workflow system. This was a good attempt to have the team working on the most valued items, but still the team hardly got things finished. The team was distracted by ad-hoc request from the stakeholders that asked them to switch to new urgent tasks before they could finish complete what they were working on before. One way to improve the value delivery of the team is create a focus in the team. We decided that the team would only take work from the PO and that he would prioritize all request from the stakeholders. For this to work it was crucial that the PO would understand his role and commit to it. I sat down with him to discuss the function the PO has in the Scrum system. Step one in the process was to gain a mutual understanding of what makes the role effective. Rather than making a function description I decided to make a mission statement. I used this to assess the drive and ambition of the employee. We are working with people after all and it’s important to assess whether the person in question likes to be a Product Owner and understands what comes with it.

Figure 1: Example mission statement of the PO

If so, the second step is an assessment of how the PO performs in the current situation. This creates coaching goals where we can work on. In this case I wanted to empower the PO to set clear priorities for the team. This implied that he had to agree to step up in the organization and say no to ad-hoc requests that came from business stakeholders approaching the team mid-sprint. Luckily, the Product Owner was open for this, and although he liked help with filling in his role, he was eager to embrace the mission statement. The third step was to anchor the role in the organization. I encouraged the PO to sit with the CEO and explain him his mission and what that would mean for the organization. Main goal of this meeting was to have a buy-in and support. We explained the CEO that when the PO would start saying no to stakeholder, they would likely complain to the CEO. After two sessions we convinced the CEO about the benefits of an empowered PO and agree that would a stakeholder complain, he would explain that the PO was doing his job. “I will tell the stakeholder that I asked for the PO to say no” The CEO concluded.

During the following sprints we had introduced sprint goals, increased predictability and the team was finishing things for the first time.

2.2 The Scrum Master: “I’d rather be a developer, but no one else wanted to do the job”

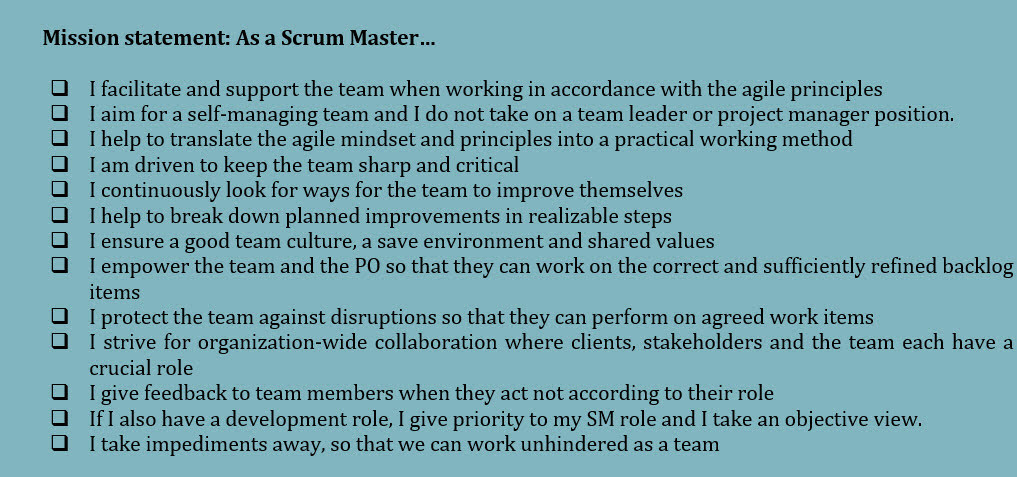

The role of the Scrum Master is interpreted in many different ways. On the high end the SM is (almost) equal to the Agile coach. On the other end of the spectrum the SM is reduced to a facilitator that books the room for the retrospective and reminds his teammates that they’re late for the standup.

One of my clients was a small bank. Within this organization the Scrum Master role was undervalued. It was implemented as a part time role that was limited to the absolute minimum. Therefore, it was not a challenging role and had low status in the organization. The Scrum Master admitted: “I’d rather be a developer, but no one else wanted to do the job.”

Analogue to the approach with the PO, we sat down to discuss the added value of a good Scrum Master. Using a mission statement we discussed the mindset and responsibilities that come with the job. “It’s not about chairing the daily stand-up, it’s about making sure team members effectively exchange information in order to meet their sprint goals” I explained. In the mission statement we deliberately used terms like empower and ensure to make a distinction between “doing” and “making things happen. We went thought each of the points and discussed the implications, challenges and also the personal growth it would lead to.

During the sessions we agreed that the SM role can be quite challenging and interesting, but when asking if she liked the described role better, she didn’t confirm. I tried to persuade her by offering to work together in making her a great Scrum Master, offered some training and coaching. But, it was a clear case. This lady did not want to be, and thus most likely would never become a good Scrum Master. Armed with better understanding of the role management started to look for a better candidate.

Figure 2: Example mission statement of the SM

Figure 2: Example mission statement of the SM

2.3 Lessons learned

In both situations I gained results by drafting a mission statement with the Product Owner and Scrum Master. We used this mission statement to align expectations and get support from management to act according to it. Additionally, describing and discussing the role enabled targeted coaching or made clear whether the person in question was the right person for the job. Both situations have in common that these were small organizations which made it was possible describe the roles without too much discussion.

3. Role Agreement in Large organizations

The next experience I would like to share is one with a large organization. I was working with four agile coaches in a department of 20+ component teams. Not one of the teams was alike. The teams were working with different techniques, systems and showed a wide variety of maturity, autonomy and culture. Some teams could work independently, while other teams were stuck in a web of dependencies and constrains. The department was led by a large management team of nine managers, each responsible for two or three teams.

The department was challenged by role conflicts between managers and Product Owners. Some Product Owners were ambitious and wanted to increase their mandate. They felt being held back and were frustrated. Some junior Product Owners were quite uncertain and relied heavily on their manager. Some managers were content experts, they acted as a Chief Product Owner (CPO) and had taken over the stakeholder management. In these cases little room was left for the PO to prioritize and own the product. Other managers were the teams hierarchical manager and, at the same time, their primary stakeholder. They were dominant in their double role. In most cases this led to frustration and did not help the teams to perform.

Based upon the successes in previous organization I was eager to pull out the mission statements again. But in this versatile setting that didn’t work. We organized a session with a few Scrum Masters and Product Owners and got stuck in the discussions. The difference with the previous experiences became clear. In the smaller organizations it was easy to get alignment on the role descriptions. In this setting, it would be hard to achieve a collective understanding and agreement. With 20+ Product Owners and 9 managers, there would always be someone disagreeing or claiming to be the exception. We played with the idea of creating a formal role description and make it mandatory, but decided not to. We wanted autonomous teams, not limit and frame them. We wanted to help each team to become more effective, not force them to comply to a standard. Additionally, we expected hard times in aligning the management team. Therefore, we left the path of creating (and superimposing) a single truth and focused on connecting and aligning each manager and PO couple. We retraced to our initial goal: empower the PO and teach the manager how to become a leader rather than manager. In the next session I describe our approach.

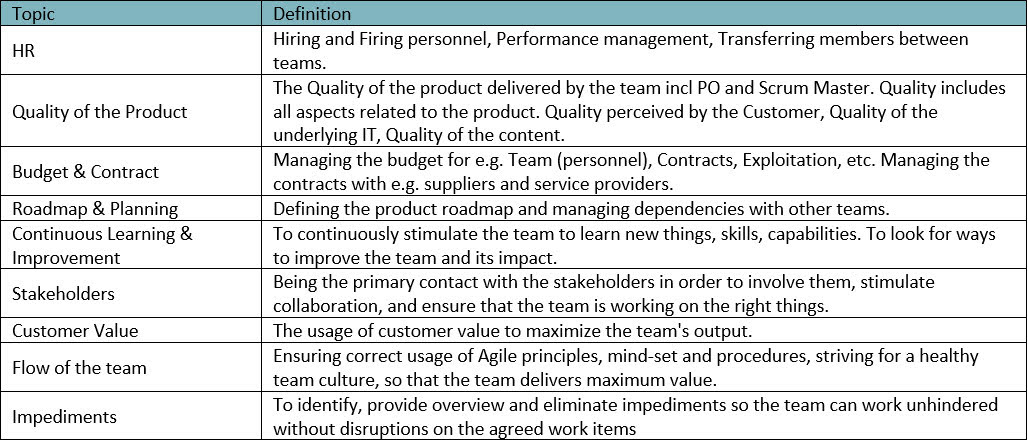

3.1 Defining topic that we need alignment on between manager and Product Owner

Rather than describing the role of the manager and the Product Owner, we identified topics where role conflicts were seen to happen or were expected. This resulted in a list of topics that we used as basis for a delegation and responsibility dialogue.

Figure 3: List of topics that we used in the delegation and responsibility meetings

Figure 3: List of topics that we used in the delegation and responsibility meetings

3.2 Delegation and responsibility dialogue: “Who does what?”

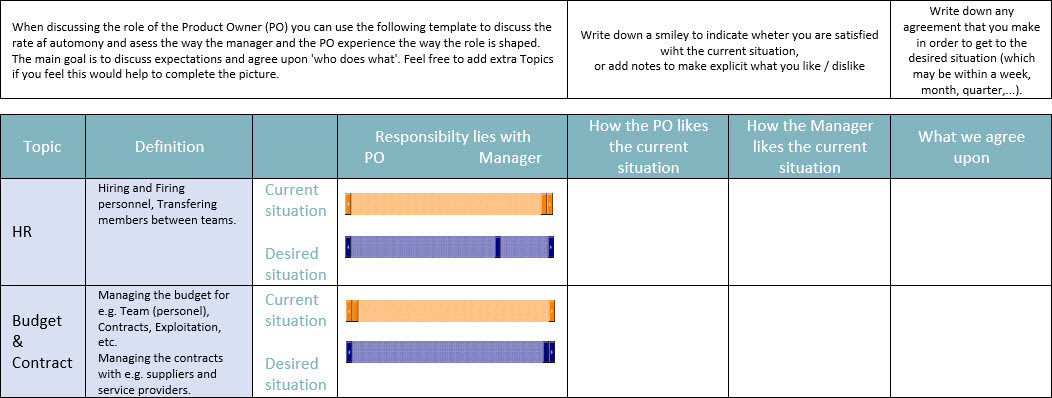

We organized a series of moderated sessions with each of the Product Owners and their manager. Since we had to have twenty sessions, we divided the task among us agile coaches. Aim of each meeting was to discuss the rate of autonomy and assess the understanding that the manager and the PO had on their own and each other’s role. These meetings created an opportunity for the Product Owner and the manager to discuss expectations and agree upon ‘who does what’.

The meetings were supported by the template shown in Figure 4. From left to right you see the topics as listed in Figure 3. Next are two sliding bars, that were used to indicate where the responsibility of this topic belongs. By using two sliding bars, one for the current situation and one for the desired situation, we created a discussion on expectations and improvements. The next three columns are for the PO and Manager to add opinions and agreements.

Figure 4: Fragment of the template used to support the delegation and responsibility meetings

Figure 4: Fragment of the template used to support the delegation and responsibility meetings

As could be expected from an organization with so much unique teams, the results of the meetings varied a lot. Some managers and PO’s were already quite aligned, and the meetings yielded little insights. Some Managers and PO had not yet taken the time for such a dialogue. These sessions helped them to get better alignment and also yielded improvements. E.g. One PO was encouraged to do more stakeholder management, and another got more mandate to handle supplier contracts. One of the managers committed himself to step out of the content and wanted to encourage the team to define their own solutions. Each of these improvements were identified and put on the coach assignment backlog. So that we agile coaches could help the PO, the manager, and the team to become more effective.

The result of the delegation and responsibility meetings was that we reduced the role conflict between the managers and the Product Owners and identified improvements that we could work on. It confirmed the wide variation that existed in the department. But rather than starting a fight over the best theoretical model, we encouraged the managers and PO’s to align with each other and define improvements. As agile coaches we volunteered to coach and monitor these improvements in daily operation. For this purpose we set up the triangle-meetings.

3.3 Triangle meetings: “Who do you think should deal with this challenge?”

The delegation and responsibility meetings were a starting point for role alignment, but the sessions were a snapshot made at one particular moment. We expected that during daily operations much more small topics would surface. So, rather than having another series of delegation meetings, we set up an experiment with more operational meetings. In order to extend the reach of our intervention we included the Scrum Master in session as well. Hence, they were called triangular meetings.

The triangular meetings were set up with two goals. The first goal was to empower the team and to ensure that the PO, Manager and the Scrum Master could facilitate the team as effectively as possible. The second goal was to guide the participants with filling in their role. As agile coaches we could observe the way the participants interacted and help them to improve their collaboration. At the same time we learned about the struggles of the team. From our position we could guide the PO, SM and Manager with finding the right solution, or engaging an experiment to learn. We could also help the participants with filling in their role. In this meeting we could also actively monitor the improvements that were identified during delegation and responsibility meetings. We could address when e.g. the PO went too much into detail or when the manager was tempted to deal with the suppliers’ contracts, etc. “Who do you think should deal with this challenge?” would be a typical question for the agile coach to ask and create a better understanding of the PO, SM or Manager role.

The triangular meeting was a meeting for the PO, SM and Manager. We put the Agile Coach in the middle as facilitator but emphasized that the responsibility of organizing the meeting was with them, not the agile coach. This enabled us to build a strong organization that did not depend on the agile coaches but on independent teams. Drawback of this was that some managers liked the setup very much and had lively regular meetings, while other managers were too busy. They couldn’t make time to have these meetings or regularly canceled them at last notice. Unfortunately, I did not manage to address this with the management team and get a clear statement on this behavior. The triangular meetings were therefore for the willing and the results of the set-up varied. Some teams strived and became better and more effective. They had a platform to discuss performance and collaboration. Some teams were stuck in their old behavior and made little progress.

Figure 5: Participants of the triangular meeting

Figure 5: Participants of the triangular meeting

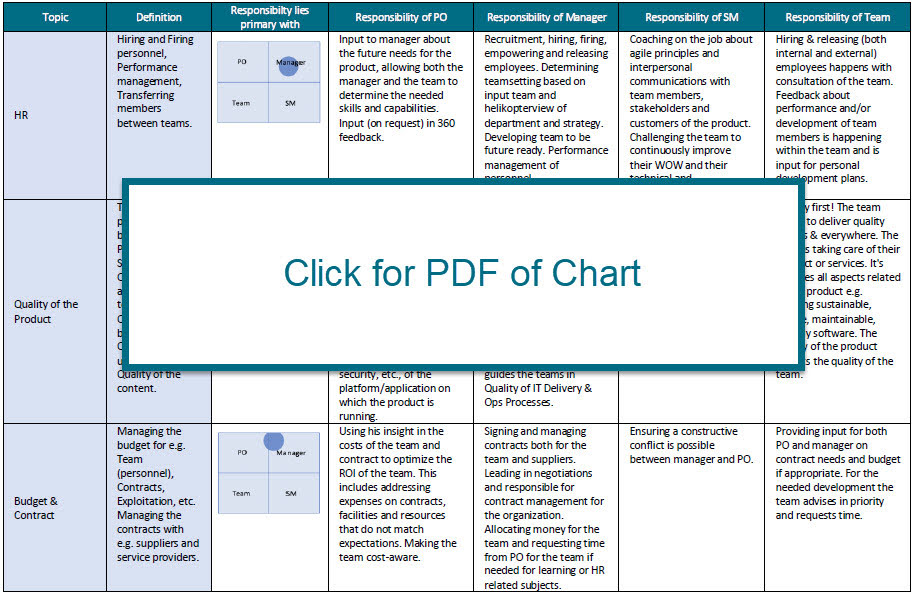

3.4 Updating the role sheet

While having spent much time on discussion the roles within this organization, I learned a lot about the dynamics between the team, PO, SM and Manager. I extended the original delegation template, with the role of the team and the Scrum Master. In Figure 6, the initial sliding bars of Figure 4 are replaced with a little graph. The blue dot indicates whether the weight of the responsibility lies with the PO, SM, Manager or the team. The additional columns each describe how each role contributes to the topic. This led to a nice reference sheet that we used in our triangular meetings or when boarding a new Scrum Master, for example.

Figure 6: Role reference sheet for the PO, SM, Manager and team.

Figure 6: Role reference sheet for the PO, SM, Manager and team.

With the sheet we aimed to go beyond the initial delegation question. As can be seen, many topics in the role sheet are shared responsibilities, and have their blue dot in multiple cells. Rather than asking “Who do you think should deal with this challenge?” we thought it more effective to seek collaboration and ask, “to what extend is this person responsible for dealing with this challenge?” Take for example the topic solving impediments. Having a Scrum Master doesn’t discharge the rest of the team from the responsibility to solve their own impediments. But especially in large organization, the influence of the team is often limited. Additionally changing ineffective procedures may cost a lot of persuasiveness and more important valuable development time. The manager could or should step in and take this responsibility if the impediment outreaches the circle of influence of a team and/or Scrum Master. But at the same time, it is the responsibility of the Scrum Master to teach the team to spot impediments and take appropriate action if resolving them gets delayed. Topics like value creation, HR and continues learning show a shared responsibility. The best implementation depends on the context of the organization, the formal processes and the maturity of the PO, SM, Manager and team. The reference sheet might need adaption to make it fit your organization, but I share it since I believe many coaches will recognize the role challenge and can use the reference sheet in their own organization. It does give you the opportunity to address the importance of clear roles and facilitate the debate between the involved parties.

4. What We Learned

Clear roles and expectations on the collaboration of the Scrum Master, Product Owner and Managers are important to effectively support agile teams. In smaller organizations it is relatively easy to get alignment on the role descriptions. In larger organizations this is much harder, since exceptions rule. Rather than striving for one truth or super imposing a one-size fits all description, we took an approach where we organized a) meetings between the manager and the Product Owner to align with each other and discuss improvements in collaboration and b) facilitated operational triangular meetings to empower the team and to guide the PO, SM and Manager to better facilitate the team according to the mission of their role.

What I liked about this approach is that we put the performance of the team in a central place and took an approach that focused on alignment and collaboration, rather than having fierce discussion to establish a single truth. We did not superimpose a role description but found a collaboration mode that enabled each team to be effective in their own context. Along the way we learned a lot about the different roles and how they are complementary to facilitate the team. The triangular meetings set the stage for further learning and improvements.

What made the approach fragile, was the variation in commitment from the involved managers. Some managers were too busy and couldn’t make time in their agenda to have these meetings, canceled them at last notice, or just did not find the agile adoption relevant enough. Learning point is that management commitment is crucial if you want to make impact and reach beyond the willing teams. In larger organization there is a large variation between maturity a motivation of the teams. Some will be more effective in embracing agile principles than others. We have to accept that.

This report described how to deal with delegation and responsibility between the roles of PO, SM, manager, and the agile team. You can imagine that with the use of scaling frameworks like SAFe® the complexity of the situation will rise. Product Manager, Product Owner, Release and Solution Train Engineer, System & Solution Architects, Business Owners and Agile Leaders all swarm around agile teams. Each with their own expectations and personal preferences. It would be interesting to see how the agile coach community copes with role conflicts in this wider context. Will an extended role sheet suffice as a good method to guide the debate?

5. Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Kelly Chai and Jeroen Bakker for their review. Additionally a big thanks for Paolo Tell from the IT University of Copenhagen for his shepherding and review. Last but not least I would like to thank the agile coaches and colleagues that I collaborated with on the described assignments. They made the story that I share in this report. Finally a big thanks for the Agile Alliance and the organization of XP2020 for publishing this experience story.