January brought bad news for Agile-haters and those, like former IBM CEO Sam Palmisano, who sneer at “firms with names like pieces of fruit.” Apple posted the biggest quarterly profit in history, with a net profit of $18 billion in the quarter, handily exceeding the previous records of $16.2 billion profit by the Russian firm, Gazprom, in 2011 and $15.9 billion profit by ExxonMobil in 2012.

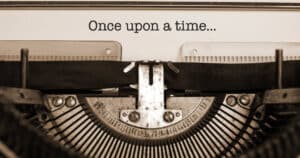

As in my previous article, I am talking here of course about Agile in the broad sense of an ideology in which individuals, teams, networks, and ecosystems are continuously delivering new value to customers in an iterative fashion.

It is easy to lose sight of the core ideology of Agile and the Creative Economy when you hear about myriad specific implementations of Agile, as depicted here in this clever graphic by Australian designer Lynne Cazaly.

Obviously there are big differences between, say, an individual Scrum team with its Product Owner and ScrumMaster on the one hand, and Apple’s ecosystem of half a million App developers, delivering value to hundreds of millions of customers through a platform.

They are not the same thing, but they are instances of the same larger concept. They are both part of the same ideology and mindset of doing work that draws on the full talents of the people doing the work and gives them a direct line of sight to the customer. It is based on the belief that if you delight by the customer, the organization itself will flourish. Making money is the result, not the goal.

At the team level, the firm is using the Product Owner as the lens or intermediary to interpret what the customer wants.

At firms like Apple, the platform enables those doing the work to deal directly with the customer.

Agile is massively scalable

By having a platform, rather than an individual (the Product Owner), serving as a lens to the needs of the customer, Apple is able to achieve massive scale, with hundreds of thousands of developers devising every conceivable App to meet the infinitely variable needs of hundreds of millions of customers. As a result, each one of those hundreds of millions of customers has a product that is individually customized to meet his or her own special needs and wants. This is something that a bureaucracy couldn’t conceivably accomplish. Nor could a single Scrum team or set of Scrum teams achieve it either.

So a single Scrum team and the Apple platform are part of the same family.

- They have the same total focus on the customer.

- They have the same ideology of enablement, rather than control: managers are enablers, not controllers.

- They have same flat horizontal structure, not the vertical structure of the Traditional Economy.

- They have the same iterative dynamic.

- They are both inspiring to the people doing the work, rather than dispiriting, in part because they draw on the full talents of the workers, not just what some boss is telling them what to do, and in part because the goal of delivering value to customers is more inspiring than making money for the boss.

Haydn Shaughnessy’s new book, Shift, gives further examples of the dynamic of Agile at scale. For instance: “Autodesk [ADSK], a leader in CAD/CAM software and building system modeling, has created a platform where companies in construction and civil engineering can draw on a growing number of apps created by an independent community. The aim is to help large construction companies simulate all aspects of a giant building project before breaking ground so they can anticipate problems and better coordinate suppliers.”

The ecosystem is massive, involving some 120 million designers and customers. As a result, Autodesk has handily outperformed the S&P500 over the last five years.

Agile isn’t easy

“Agile is not for the faint at heart,” as one reader, John Mereness, commented on the first part of this article. “The dollar losses (among other losses) for the first few attempts (which are likely to fall flat on their face) can be very high. I think nothing of hearing the horror stories of failed Agile implementation. The stories come out of large organizations, and small as well, who really made the effort to ensure that Agile succeeded – and it failed nevertheless). That being said, if the companies/people are dedicated and persistent, they will get to the goal (and that goal far exceeds any losses/failures along the way). And, when they get that first successful project, it is the same as Alexander Graham Bell inventing the telephone or Thomas Edison turning on the first light bulb.”

Nor should we be distracted by the fact that there is a lot of fake Agile around. As another reader wrote, there is often “a thin Agile veneer laid on top of traditional corporate hierarchy and politics.” Often Agile can be “a bit of gold plating that makes the business feel self-important.” In these cases, “companies are doing what they’ve always done; they’re just now calling it ‘Agile’.”

But when firms make it through the difficult transition period, and take the ideology to heart, and implement it on a consistent basis, not merely adding a veneer of words, then they get the kind of results that we see at Apple, Autodesk, Alibaba and elsewhere.

Continuous deployment

In another variant of Agile, sometimes known as “continuous deployment” or “DevOps”, the distinction between development and operations disappears. For instance Etsy.com, the rapidly-growing billion-dollar online market deploys more than 30 software improvements each day. By having very frequent releases of small changes, it’s easier to spot and fix problems than when a problem emerged in a release that was a bundle of many changes and it became difficult to figure out exactly where the problem was. Instead of management approval being required for all changes to the actual site, now all improvements that have been fully tested are deployed immediately. The same staff devising the improvement oversee implementation.

Instead of a separate “deployment army” to cope with each new release of bundled change, now the same staff who are devising the improvement oversee the release: this improves mastery and autonomy. The long days and late nights of the developers at Etsy are largely gone. Also largely gone is “scheduled downtime” and prolonged outages. With an average of 30 innovations to the website deployed each day, it is innovation on steroids. Each of the changes is small, but a small change can be significant, sometimes adding millions of dollars in sales. Doing all this change in tiny increments at warp speed within the framework of a central strategy enables extremely rapid innovation and learning, as well as much greater facility in spotting and fixing any problems that may emerge.

A Copernican revolution in management

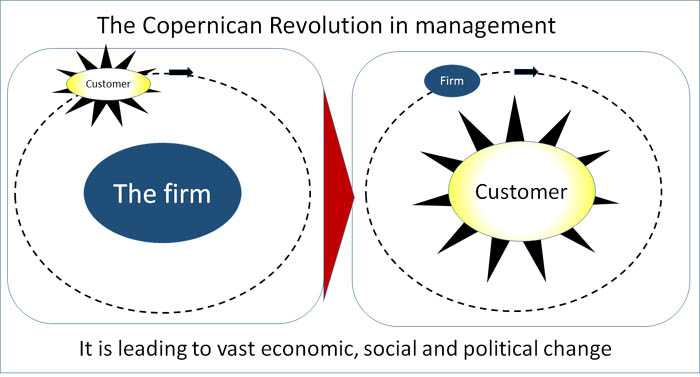

Agile and the Creative Economy thus comprise a large core idea, with many different implementations. The core idea is not just a new process or methodology, but a different ideology – a different way of viewing and acting in the world. Instead of an ideology of control with a focus on efficiency and predictability and detailed plans and internal focus, it’s an ideology of enablement, with a focus on self-organization, continuous improvement, an iterative approach, and above all, the customer is now central.

A shift in ideology isn’t a little fix, like adding a marketing department.

It’s more like the Copernican revolution in astronomy. Prior to Copernicus in the 16th Century, people imagined that the sun revolved around the earth. It was self evident and confirmed every day by what everyone could see. Everyone knew that the sun revolved around the earth. After Copernicus, people realized that it was the other way around. Despite appearances, it’s the Earth that revolves around the Sun.

And as Thomas Kuhn pointed out in his book, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1957) this wasn’t just a discovery in astronomy. It had vast economic, social, and political consequences. People began to ask: is it really plausible that the Roman Catholic Church is the center of the universe? Is it plausible that kings and queens govern by divine right? It began to put in question and eventually alter the entire structure of society.

The ongoing shift in management today is of a similar nature and magnitude.

In traditional management, the firm was the stable center of the universe and the customer revolved around the firm. The customer was taken for granted.

In the new scheme of things, the customer is the center of the universe and the firm revolves around the customer.

Instead of managers asking “How can I get customers to take what we make?”, now managers have to ask, “What are the unmet needs of the customer that I can find ways to satisfy?”

Instead of managers asking, ‘How much more can we sell?’ now they have to ask: ‘What else does the customer need?’”

With these new questions, the guy at the top of the hierarchical pyramid doesn’t necessarily have the best knowledge any more. And so as in astronomy, a whole series of questions start to be asked the structure of corporations and indeed of society in general. Why should that guy be telling the workers what to do and get paid so much when they know more and better than he does?

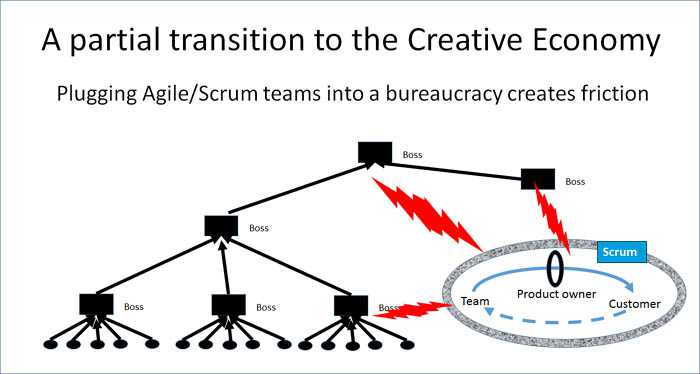

So this transition is now under way at the team level, with hundreds of thousands of Agile/Scrum implementations all around the world.

But it is also happening at the level of the firm, as hierarchical bureaucracies transition into more agile more modes of operating, with firms like Apple, Google, Alibaba, Autodesk and so on.

The tension between Agile and traditional management

And as we saw in the poll that I mentioned in the first part of this article, there are many partial transitions, where one part of the firm is solidly entrenched in hierarchical bureaucracy, while another part of the firm is operating in the new mode with Agile and Scrum and Lean and DevOps and Continuous Development and so on. When you have those two different ideologies operating in the same organization, it’s not surprising that there is a lot of friction.

In those situations, the two parts of the organization are operating with different ideologies. They are not just getting different answers. They are asking different questions. They are operating with different understandings about how the world works.

A paradigm shift in management

So managers need to recognize that they are dealing with a paradigm shift in the strict sense laid down by Thomas Kuhn involving basic shift in our understanding about how the world works. Of course, the phrase “paradigm shift” has been thrown around in management for such a long time that it has become something of a joke. That’s because the claimed paradigm shifts always turned out to be “more of the same.” Gurus cried wolf too often. But now it turns out that we have a real wolf on our doorstep.

Now we are dealing with a genuine paradigm shift. It’s different way of understanding how the world works. This insight can help us understand why the new way of managing in the Creative Economy is having problems getting accepted, despite its advantages.

Thomas Kuhn in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1957) explained that paradigm shifts work in four phases:

Phase 1: “Normal science” proceeds, on agreed assumptions

Phase 2: Anomalies appear, and “fixes” are introduced but they don’t fully solve the anomalies.

Phase 3: Forward thinkers recognize need for fundamental change

Change is strongly resisted by the powers-that-be

Long-standing attitudes, values, assumptions support the status quo

Phase 4: The new paradigm is generally accepted

We are right in the middle of Phase 3 of a paradigm shift in management.

Forward thinkers in management now recognize need for fundamental change. But change is being strongly resisted by the powers-that-be and long-standing attitudes, values, and assumptions support the status quo. We need to recognize that this is normal in Phase 3 of a paradigm shift.

Such shifts can take a long time. Thus it took the Roman Catholic Church three hundred years to change its mental model of the world and remove the ban on even discussing the idea that the earth revolves around the sun.

With management, it’s not going to take 300 years, because the economics are forcing change. The old way of managing is becoming less and less productive, and the ongoing disruption of existing business models demonstrates. Once you get behind the booming stock market, built on cheap government money and financial engineering, you find that the rates of return on assets and on invested capital of US firms have been on steady decline since 1965. Firms which are run in the old way are being put out of business. The options are basically: change or die. Some firms are opting to die. But the change will happen regardless.

So the question is not whether the transition is going to happen. It’s when. The question is: will the change be agonizingly slow and ugly and bloody? Or will it be quick, elegant, and intelligent? The movement towards the Creative Economy, with Agile, Scrum, Lean, DevOps, and its analogs, is about generating the latter outcome.

Copyright © 2015 Steve Denning | This article first appeared on Forbes.com in January 2015 and is republished here with Steve’s permission.

![[Case Study] Lessons from descaling 25 Scrum teams](https://www.agilealliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/descaling-teams-1200x630-1-150x150.jpg)

![[Case Study] Lessons from descaling 25 Scrum teams](https://www.agilealliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/descaling-teams-1200x630-1-300x158.jpg)