Abstract

Change has changed. The amount of information and speed of information flow have outpaced our organizations’ abilities to filter and make sense of available facts and take good decisions. Therefore, we need to look at our decision making systems and optimize them to meet today’s challenges. Traditional management hierarchies are especially struggling with this. Agile approaches provide a good starting point, but often come to a limit when agile is hitting the constraints imposed by traditional hierarchies. In many cases, this is perceived as a choice between either strong hierarchical leadership and low participatory decision making or weak hierarchical leadership and strong participatory decision making.

The good news is, that this doesn’t have to be an either-or decision for one of these two perspectives. Combining Agile with ideas from Sociocracy provides us a way to create alignment between Agile ecosystems and the business needs of strong leadership and a clear hierarchy.

Table of contents

- Introduction

- Management, Leadership and Decision Making

- A closer look at the challenges

- Decision Making in Agile Teams

- The friction between Agile and Management policy making

- The sociocratic approach to resolve the tension between hierarchical and participatory decision making

- Resolving the tension between Agile Team and Management Team policy making structures

- Summary

- Case Studies

- Annex

Sociocracy in a nutshell - Footnotes

- The Authors

1. Introduction

Starting an Agile adoption in a larger organization is always a stepwise approach. You cannot define “the Agile process” and then roll it out in a big bang, because Agile is not about processes and tools, but about individuals and their interactions when they collaborate in a certain ecosystem. So even if you employ a revolutionary approach with some teams or products, the organization will change step by step.

One of the inevitable side effects of this stepwise adoption is the coexistence of traditional and Agile cultures within the same organization. This usually leads to typical friction and conflicts. The Agile teams complain, they don’t feel empowered enough, while managers and staff personal encumber themselves that “Everybody does, what they want. we’re losing control”. We have seen adoptions failing because of an escalation of this conflict.

Looking closer at this conflict from a neutral perspective reveals that the core argument is about the way decisions are made in the organization. This is good news, because decision making is a well-understood topic in organizational development. If we understand the different decision making models, that the parties in this argument have in mind, we can find constructs that work for both sides.

1.1 Management, Leadership and Decision Making

Most companies today are still organized as hierarchies as the predominant organizational approach. This structure was invented 100s of years ago helping societies and organizations to become more productive. In a hierarchical organization we have appointed, formal leaders with a clearly assigned responsibility and authority (usually called “managers”).

At the same time, the world has developed and looks quite different than at the time hierarchies were invented. For a long time, the hierarchical approach could cope with that development, but the time has come where we see more and more of these organizations struggle with change. What happened?

As a number of people have found, change itself has changed (see e.g. Gary Hamel1). Change is happening faster than ever before. That in itself has been a prevailing phenomenon for quite some time, but change of the outside world has become faster than hierarchical organizations can follow internally.

A root cause is the increased speed at which new information is spread. Hierarchically structured organizations assume, that the appointed leaders with their responsibility and authority are able (possibly after consulting co-workers) to take well-informed, sound decisions. However, with the emergence of the internet and the wide spread of mobile communication technology, the number of information providers and spreaders has grown exponentially. Anybody can be a content or information provider. Everybody can learn from everybody. There are tons of information and also tons of mis-information.

Digesting all available information, filtering the facts, making sense of it to take the needed high-quality decisions is a bigger challenge than ever. The amount and speed of information availability has exceeded human – and organizational – capabilities to cope with it.

Of course companies are reacting and adapting to this increasing challenge. As an effect, decisions get more and more distributed in today’s organizations. It would just take too much time in our fast-paced world to get all decisions made or approved by formal leaders only.

So, many informal leaders emerged. We can see from our companies, that essentially anyone in an organization could take leadership and drive decision making within an area. This is sometimes done in a well structured way, for example via clearly defined roles. Often, however, these non-appointed leadership roles are not empowered well in the hierarchy.

Decisions taken at a lower level in the hierarchy or made by the informal leaders can be overruled by appointed formal leaders. This creates misalignment, frustration and disconnection and it works against people taking the lead within an area. In effect it makes organizations slow: in extreme cases of traditional hierarchies, people are not incentivised to take own decisions, so they learn to better ask for permission from a formally appointed manager or people just wait for the manager to decide.

Companies, that learn how to distribute decision-making and make it more effective, have a significantly better chance to keep up with today’s speed and thus be commercially successful.

1.2 A closer look at the challenges

The speed challenge

Today’s need for speed is very difficult to achieve using traditional organizational setups. Decision-making in traditional hierarchical structures means that people in the company need to turn to their bosses for permission and decisions on expected things. Due to the high pace in the modern world, that has two consequences:

- Bosses get overloaded with requests to take decisions or provide guidance

- Consequently, decisions and guidance come relatively slow.

To gain speed organizations need to start empowering people to act and decide locally and autonomously.

The autonomy challenge

The obvious next question is: doesn’t it result in big chaos when everyone can take their own decisions? Of course it can. But that question is not a constructive one. A more constructive question would be: what is needed, to enable people and teams to take their own, local decisions in such a way, that we do not end up in a chaos on company level?

The answer is: alignment. If people and teams are aligned on the overall vision and direction, they can take their own decisions without creating a big chaos.

The alignment challenge

So, how to create alignment? And: what to align on?

Generally, alignment can only be achieved if people have constructive interactions. So you need a structure enabling the needed interactions and a culture of sharing diverse perspectives, discussing them respectfully and coming to joint conclusions, that everybody can and will carry forward. That structure and culture can then be used to first agree on what needs to be aligned on and then start aligning.

How could that work practically? In fact this is not a new challenge. The Sociocracy community is dealing with these problems since the early seventies of the last century, so it’s worthwhile to look at an agile enterprise through the models and tools developed by the Sociocracy initiatives (have a look at the appendix “Sociocracy in a nutshell”).

2. Decision Making in Agile Teams

The primary goal of agile approaches is to enable fast actions in dynamic and unpredictable environments. According to the research of the past forty years, self-organization is one of the strategies here. It allows fast adaptation and resilience to change on one side and the stability needed to develop and run large systems on the other side2. Consequently all agile approaches are designed to foster self-organization.

There are several ingredients a system needs to develop self-organizing behavior:

- You need a minimum number of independent actors.

- These actors need to maintain open bi-directional interactions that allow them to exchange information they don’t expect.

- You need sufficient diversity among these actors to allow a productive tension generating the ability to change.

- You need enough alignment on a (business) goal to make sure that the diversity does not lead into uncoordinated chaos.

So the balance between autonomy and alignment is one of the key-factors in any Agile organization, enabling the speed of adaption. Too much autonomy or too little alignment lead to unproductive chaos. Lack of autonomy or too detailed alignment lead to loosing the dynamic adaptability of agile teams and thus one of the core business values you get from Agile.

Agile uses team collaboration as the primary method to create alignment and ensure communication. This is in contrast to a centralized workflow breakdown in traditional organizations done by process engineers who are not part of the delivery teams. The team plans together, communicates at least on a daily basis and celebrates success together. And the team is also responsible to set appropriate policies, such as the Definition of Done.

Policies are set via Retrospectives

The core practice of agile teams to find and maintain their policies is the Retrospective3. How this is done is not strictly defined, but a large body of techniques has developed over time, many of them adapted from existing material on participatory decision making4. In particular the method of decision making is chosen as part of the facilitation process. Majority votes, consensus decisions and veto rights are typical ways to come to a group decision.

Mature Agile teams usually have developed a strong culture of retrospectives: They have led them to a good alignment on both their goals and their policies and to a strong notion of responsibility for their policies. Often they develop new terminology helping the team to catch the essence of their discussion. When Spotify talks about “Bets” rather than “projects”, their home-brewn terminology expresses rich and broad meaning to those who have been involved in the creation of their organization. Just copying the terminology without having gone through this discussion is prone to “Cargo Cult” – the pointless duplication of external form without grasping its essence.

So even though Agile teams often take significant effort to make their policies explicit, they also gather a lot of tacit knowledge, usually referred to as their team culture.

3. The friction between Agile and Management policy making

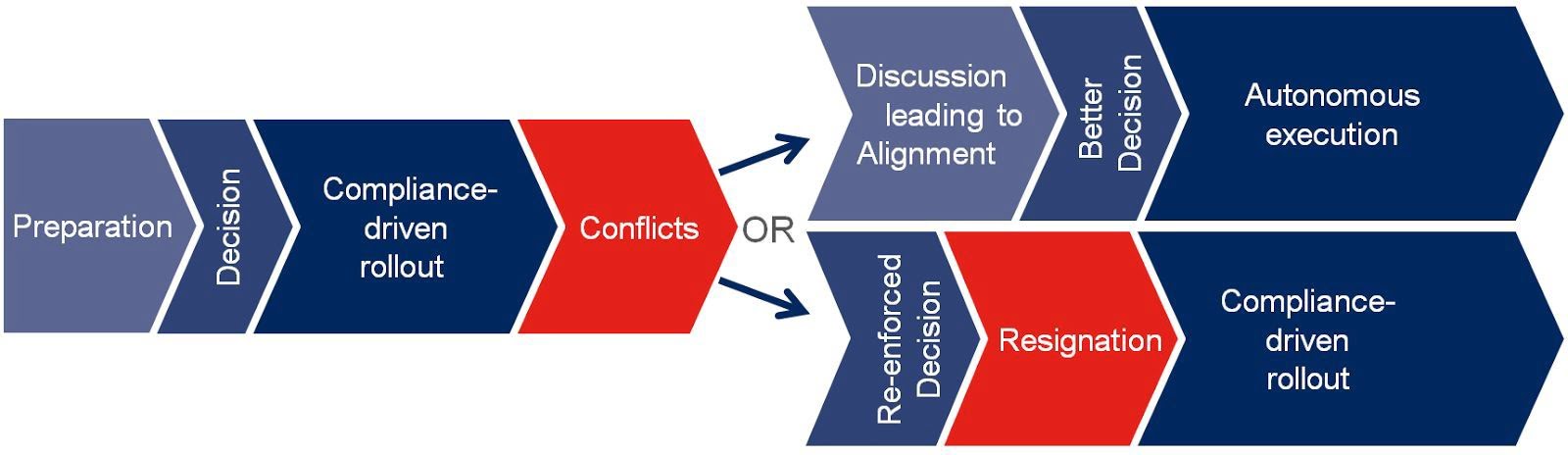

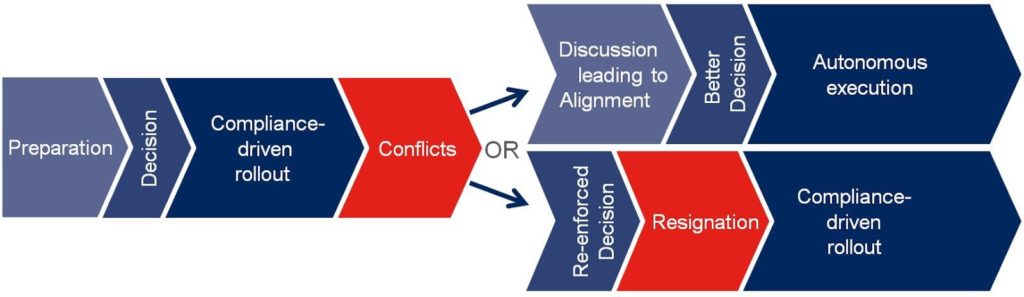

The hierarchical approach to taking decisions is usually happening as outlined in the following figure:

After a preparation (by a couple of experts who make a proposal for decision), the decision is taken and a compliance driven roll-out is started.

After a preparation (by a couple of experts who make a proposal for decision), the decision is taken and a compliance driven roll-out is started.

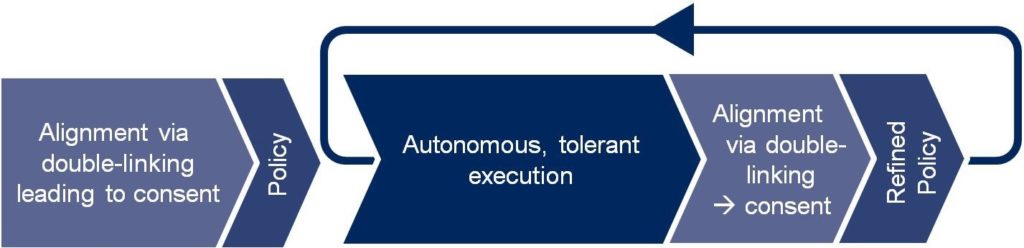

Agile prefers an alignment-for-autonomy approach as shown in the following figure:

After an alignment phase, where a joint proposal is created, a decision is taken after which execution can be done autonomously. Usually the discussion and alignment phase of agile teams takes more time and effort than the analysis and preparation phase of hierarchical teams. This creates the – wrong – notion of hierarchical decision making being “more efficient” than participatory decision making because the time-to-decision is shorter.

After an alignment phase, where a joint proposal is created, a decision is taken after which execution can be done autonomously. Usually the discussion and alignment phase of agile teams takes more time and effort than the analysis and preparation phase of hierarchical teams. This creates the – wrong – notion of hierarchical decision making being “more efficient” than participatory decision making because the time-to-decision is shorter.

Why wrong? Let’s look at what we have observed in reality:

If you start from a hierarchical decision making approach, you often run into a conflict phase during the compliance driven rollout:

This is because the people, who have been part of the preparation phase, often miss some of the more detailed insights the teams have. So, when the teams are confronted with the decision, they might find it suboptimal from their perspective, which leads to discussions.

This is because the people, who have been part of the preparation phase, often miss some of the more detailed insights the teams have. So, when the teams are confronted with the decision, they might find it suboptimal from their perspective, which leads to discussions.

Often that leads to an alignment phase where the teams’ insights are used to create a better decision.

If you start from an alignment-for-autonomy approach, often the alignment does not consider the full picture:

As a consequence, the alignment is more a local alignment. After the decision, conflicts arise during the autonomous execution because the managers in the hierarchy observe issues with the “big picture” view. However, since the decision is based upon alignment, changes come faster and more in the spirit of the original idea, than with a compliance-driven roll-out. The alignment-for-autonomy approach therefore allows fast adaptation.

As a consequence, the alignment is more a local alignment. After the decision, conflicts arise during the autonomous execution because the managers in the hierarchy observe issues with the “big picture” view. However, since the decision is based upon alignment, changes come faster and more in the spirit of the original idea, than with a compliance-driven roll-out. The alignment-for-autonomy approach therefore allows fast adaptation.

What we learn from this:

The disconnect between teams and managers in the hierarchy slows down decision making and execution and wastes a lot of effort in conflicts. This is, because management and teams have divergent perspectives on the topic. If we let the teams decide on alignment the management perspective can be lost. And if we let management decide, the team perspective may be lost. The problem is that we miss a place to have both perspectives at the table and that doesn’t get better by the two parties not talking to each other.

From a speed point of view, the hierarchical, compliance driven decision making approach, has disadvantages compared to the alignment-for-autonomy approach. That is because the alignment-for-autonomy approach in principle embraces the element of “we need to do this together.”

So, the question is: how can we optimally implement an alignment-for-autonomy approach in a hierarchically organized company? And that means: how can we avoid “local-only” alignment and always create a “global” alignment where needed, making use of the big-picture view and the local views.

4. The sociocratic approach to resolve the tension between hierarchical and participatory decision making

Often leadership and hierarchy are perceived as the same. Although these are different concepts in our opinion it is often seen as that we have to choose between either having strong hierarchical leadership and weak participation in decision making or strong participatory decision making with weak management. We believe, this is the wrong perception: This either-or perception may lead to not fully grasping the benefits of both approaches: neither of the higher quality and commitment of the participatory decision making nor of the speed and control (coordination) coming from a clear hierarchy and strong leadership. Sociocracy has developed a third option enabling decision making structures with both strong hierarchical leadership and strong participatory decision making with autonomy.

- A first step is to distinguish between policy and execution. Policies are the general agreements on the what, when, how and who, that set the boundaries and provide the mandates for the persons responsible for the execution of that policy. Thereby allowing for autonomy in execution. It also offers the possibility to delegate decision making authority to lower level units, who can then make their own policies within the delegated framework.

- Second, policies are decided upon in a participatory way to ensure alignment and the quality of the policy. This needs the non-trivial organizational skill to run discussions on policies that finally lead to an alignment. The execution is delegated to one or more team members who are free to take autonomous decisions within the boundaries of the aligned policies.

- Third, make use of the principle of governing consent for the participatory decision making on policies. Consent means no paramount reasoned objection. It is not a veto and not the same as consensus (see appendix “Sociocracy in a nutshell”). The main question here is whether you do agree enough to be willing and able to execute the proposed policy. Governing consent means that any decision making principle is allowed (autocratic, chaotic, majority vote, consent etc.) as long as it is decided upon with consent.

- Fourth step is applying the consent principle also to the distribution of roles and tasks. Including the leadership role. To have a leadership can be very helpful to do the day-to-day coordination of work. Like a conductor of an orchestra who by taking care of regulating the coordination between the different musicians and taking care of other collective parameters like speed, loudness, the composition, helps the individual musician to be able to focus on leading and executing his part of the play. These conductor-like roles are useful leadership positions for a team because they allow others to concentrate on their part of the job. Who will hold this supervisory position and what will be the scope of his or her mandate (decision making domain) is a policy decision (see appendix “Sociocracy in a nutshell”).

The concept of consent deserves some more attention.

Consent is faster compared to consensus decision making since it does not require an alignment of preferences but rather an alignment of tolerances.

How much tolerance will we allow for the execution to make sure we will be aligned enough? This brings us to a very important aspect of sociocracy: tolerance must be. Without it, policies become a straight jacket telling you exactly what to do when and limiting your ability to deal with the unpredictable nature of life (including work) (see appendix “Sociocracy in a nutshell”). So if participants have objections to a proposed or existing policy we want to know if these are paramount: being out of their range of tolerance. Therefore preventing the person from being willing and/or able to execute the policy.

There is another important aspect here: Tolerance is not carved in stone. Most people are way more tolerant about things in which they have been involved than about things they just become exposed to. So the discussion process itself helps to broaden the tolerance of the involved individuals, making it easier to find an acceptable solution for everyone5.

If paramount objections do exist it does not imply that decision making comes to a halt, like with a veto. We will try to solve them together by gaining a better understanding through finding out the reasons behind the objections. With this knowledge we can enter into opinion forming on what to do with them. Sometimes it is enough that other participants explain how they expect to be able to deal with the issue in the execution. Then there is no need to change the policy. But it could also lead to an improved proposal which has every member’s consent. For example: doing a trial period.

In fact, this is a continuous, iterative process. Periods of autonomous, tolerant execution are followed by (re-)alignment meetings, where new insights and practical experiences are used to refine policies, to consent on new policies and to remove policies, that are found to be obsolete.

By using the consent principle for participatory decision making on policies and delegating their execution to team members we are able to distribute decision making mandates to each other. Mandates that allow team members to execute certain policies but also mandates for the leadership of the team. By doing so we combine strong participatory decision making on policy with strong self organization and ‘strong’ leadership positions in execution. Through the combination of joint policy making and the consent principle we will be able to regulate the balance between the need for autonomy and self-organization with the need for leadership.

This principle matches nicely with the Agile practices of having retrospectives to set policies and other meetings to coordinate day-to-day work, though few organizations explicitly use the consent principle.

So far about teams. However, most organizations will consist of more than one team. Usually you have multiple departments each consisting of multiple teams. How do you achieve an efficient mechanism of joint decision making to create alignment on policies between teams? For this we need a hierarchy, meaning a next level of decision making where teams can align their policies both with their common goal and with policies coming from next higher management levels.

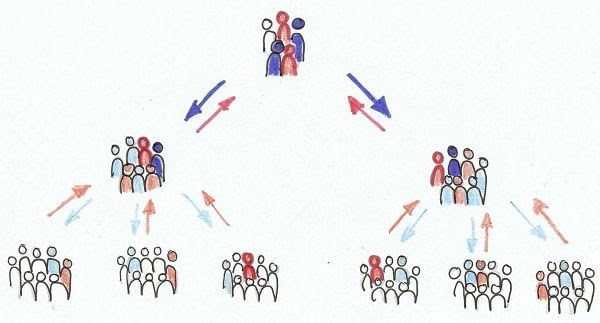

This raises the question how to ensure that these policies are accepted and get executed by the teams. The sociocratic solution is to create a double link between the levels: a team representative to ensure acceptance of policy set at the next higher level by the team and a team leader to ensure execution of policies set at the next higher level by team. Both participate in the next higher level policy making meetings. Also these policies are made with the consent principle.

The representative, a regular team member, is chosen with consent of her team. Her role is to measure if the policy set at the next higher level is executable by her team. If not she does not consent and she will explain why. Her leadership’s role is to care that once a policy is made at the next higher level it gets implemented at the next lower level, i.e. her team.

The double link makes hierarchies circular instead of the existing linear hierarchies. Circular means that there is both a bottom up (representative) and top down (leadership) connection. This allows for better alignment between hierarchical levels through an improved flow of information, feedback and the possibility to adjust. Alignment and compliance become a shared responsibility of both the lower and next higher management level.

5. Resolving the tension between Agile Team and Management Team policy making structures

Agile with its focus on collaborative decision making, self organization and iterative processes, builds an excellent foundation for creating alignment within the agile part of the organization. It has however trouble expanding these to more traditional parts of the organization, usually using hierarchic approaches for policy setting. So organizations keep agile for alignment within teams while relying on the leadership hierarchy to create alignment in the rest of the organization. As described before, the interface between these two parts of the organization is a steady source of conflicts.

The sociocratic approach offers us a pragmatic way to connect hierarchical decision making with agile participatory decision making creating the possibility to satisfy the needs of both. In this approach alignment is created via consent decision making on policies at each organizational level.

In the policy making at each level the leadership plus a representative of each unit at the next lower organizational level participate (“double link”). This combination of consent decision making on policy and the double link increases the quality of alignment throughout the hierarchy.

At the interface between agile teams and a traditional organization, this double linked circle could comprise of the responsible manager plus a representative from each agile team, deciding on relevant policies using consent.

6. Summary

The increased speed of change and rising flow of information combined with the growing complexity of our products and services challenges the decision making structures of our organizations. In order to gain speed they will have to give autonomy but in order to deal with complexity also alignment is needed otherwise the organization will end up in chaos.

Many organizations rely on leadership hierarchies to maintain a balance between autonomy and alignment. They are good in governing larger organizational structures and (in theory) allow for fast decision making through a clear distribution of authority. However, faced with increasingly complex situations decision making in a leadership hierarchy may result in weak alignment which is often compensated for with a compliance driven roll out of decisions.

After a while conflicts pop up leading in a worst case scenario to further compliance-driven roll out with a possible resignation of employees or at best in some kind of consultative decision making in order to repair the decisions and to achieve better alignment and better implementation.

The sociocratic approach offers us a pragmatic way to connect hierarchical decision making with agile participatory decision making creating the possibility to satisfy the needs of both. This collaborative decision making may then be expanded to all levels of the hierarchy, providing a smooth path to a more participatory organization.

The Sociocratic approach offers interesting ways to combine collaborative and iterative decision making on policies with a clear hierarchy and empowerment of employees (also management) authorized to autonomously execute these policies. It can help organizations to deal effectively with the speed-autonomy-alignment challenge in ways that matches both well with Agile practices and values and the management hierarchy.

7. Case Studies

There is a separate paper titled “Decision Making Systems Matter – Case Studies”. It describes case studies demonstrating how the approach outlined in this paper can be used in practice. That case study paper will be available from the same source as this paper.

8. Annex

Sociocracy in a nutshell

Sociocracy in its current state was developed in The Netherlands by the Dutch entrepreneur Gerard Endenburg. He implemented and further developed it in Endenburg Elektrotechniek, an electronics firm of which he was ceo. Nowadays hundreds of organizations use it worldwide with thousands of people. The core of Sociocracy are four rules for the design of dynamic-cyclical structures:

- Consent governs decision making: a decision is taken when there is no paramount reasoned objection to it. Which is different from consensus because it does not ask for zero objections. Nor is it the same as veto since it requires reasons to explain the objection. Consent implies both participation in decision making and being responsible for it. All other decision making principles are allowed, like majority vote or the leadership decides, provided that the decision to do so is made with consent. This leaves room to delegate decision making.

- The organization is built up of circles. A circle is a functional unit, consisting of people working towards a common aim that expresses the function of that circle. It organizes its own policy making and delegates the execution of that policy to one or more of its members.

- Circles are double linked: each circle is connected to a next higher circle by its leadership and at least one representative. The representative is chosen by the circle he or she represents. Both participate in the circle meeting at the next higher level.

- The open election of persons for functions and tasks. The circle decides with consent how to distribute functions and tasks. If the actual distribution is done during the circle meeting it is through an open discussion and decided upon by consent.

The picture below explains the concept of the double link. Each circle sents its leadership and a chosen representative to the circle meeting at the next higher level. The leaderships provides the top down connection (blue arrow): seeing to it that the policy set at the next higher level is implemented in his or her team. Whereas the representative (red arrow) makes the bottom up connection by seeing to it that the information coming from his or her team is taken into account in the policy making at the next higher level. Thereby ensuring that the levels in the organizational hierarchy become equivalent in decision making. Which makes the hierarchy better steerable and agile.

Picture made by Jutta Eckstein

9. Footnotes

1 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aodjgkv65MM

2 John Holland: Emergence – From Chaos to Order, Oxford University Press, 2000

3 Kanban doesn’t use the notion of a single retrospective but rather splits different aspects usually discussed in retrospective into the different meetings and reviews of its “Seven Cadences”. For the matter of simplicity we will stick to the term retrospective in this paper

4 See for example: Sam Kaner et.al. – Facilitator’s Guide to Participatory Decison Making, 2nd ed., Jossey-Bess, 2007

5 This requires a culture of openness in the organization: people need to be able to speak up and voice their opinions and views.

10. The Authors

Hendrik Esser

Hendrik Esser started at Ericsson as a SW developer and grew into technical coordination and System Development roles. A broad interest in people, technology and management of large organizations brought him into leadership roles, heading Systems- and Technology Management-, Testing- and Project Office organizations. Today, he heads the Operations staff unit for a very large, internationally distributed SW development organization. In 2008 he was a key contributor to the agile transition of the 2000 people organization he worked in. He supports the Ericsson enterprise transformation towards lean and agile by challenging, consulting and teaming up with other parts of Ericsson. He also is a frequent speaker at agile conferences and events and as the director of the Agile Alliance’s Supporting Agile Adoption initiative.

Jens Coldewey

Jens Coldewey is Agile Coach, Accredited Kanban Trainer (LKU) and Principal Consultant with improuv GmbH in Munich, Germany. He has more than 18 years of experience with Agile approaches and is certified as Kanban Coaching Professional, Human Systems Dynamics Professional, Certified Scrum Practitioner. As early as 2003 he was member of the board of the Agile Alliance and later has worked in the “Supporting Agile Adoption” working group of the Agile Alliance. Jens is Senior Consultant at the Agile Product & Project Management Group of the Cutter Konsortiums, Boston, USA

Pieter van der Meché

As a sociocratic management consultant Pieter van der Meche increases commitment and fosters effectiveness and cooperation within organizations and teams. Over the years he has trained and counseled in different sectors of the economy, from the shop floor level up to the board room. Mainly in The Netherlands and the German speaking countries. Employed at the Dutch Sociocratic Center since 1995 he is currently responsible for the Northern and Eastern Europe Division of the Sociocracy Group and the education of sociocratic experts towards certification. ‘Helping organizations and teams work with decision making structures based on equivalence unleashes their potential’. [email protected], www.thesociocracygroup.com, www.sociocratie.nl

![[Case Study] Lessons from descaling 25 Scrum teams](https://www.agilealliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/descaling-teams-1200x630-1-150x150.jpg)

![[Case Study] Lessons from descaling 25 Scrum teams](https://www.agilealliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/descaling-teams-1200x630-1-300x158.jpg)